Why John Cassavetes Is a Production Pioneer

The year is 1956. The radio crackles as Jean Shepherd, the host of Night People, introduces his next guest, a 26 year old actor promoting his latest film Edge of the City. Little did Shepherd know that crowdfunding as we know it was about to be invented.

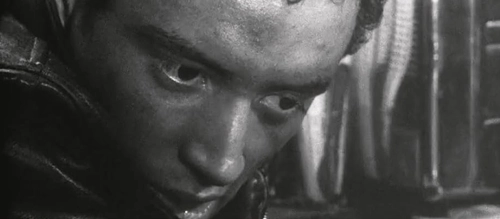

In what has now gone down as the stuff of legend, John Cassavetes managed to finance his first feature film, Shadows, off the back of a radio show. What began as a tirade about the superficiality of Hollywood ended with the young actor asking listeners to send him money to prove that he could make a better picture if only he had the means to do so. To everyone’s amazement, money started to trickle in and Cassavetes wound up walking away with $2,000 from the stunt. The rest of the film’s modest $40,000 budget was made up of contributions from William Wyler, Hedda Hopper and Robert Rossen, as well as a large chunk from Cassavetes himself.

This was to set the tone for Cassavetes’ entire career, one marked by innovation, scrappiness and an undying commitment to making truly authentic films. Of the twelve feature films he directed, seven were self-financed, earning him the much-deserved title, the Godfather of Independent Cinema. Nowadays, the low-budget Sundance darling turned summer hit trajectory is a dime a dozen, but back in the late 50s, in an industry entirely comprised of five major studios, independent cinema was quite literally unheard of.

So how exactly did Cassavetes manage to pull off funding seven features? Not without significant struggle and a lot of favours. He owed much of his success to his band of long-term collaborators who were willing to work for next to nothing, often chipping in their own hard-earned dollars from larger studio projects to fund his vision. Actors often doubled up as crew members, and many of the films were shot and edited in the home he shared with wife and muse, Gena Rowlands. This insular approach to filmmaking infuses his movies with a one of a kind, maverick spirit incomparable to anything else before or since. First and foremost an actor, Cassavetes wrote for actors, often allowing scenes to run for far longer than was conventional. A bathroom scene in 1970’s Husbands runs for 30 minutes straight.

In the documentary, The Making of Love Streams, which chronicles the shoot of his final independent film, Cassavetes comments on his approach to filmmaking: “A movie tries to pacify people by keeping it going for them so that it’s sheer entertainment. Well, I hate entertainment.” He never conformed to the rules of Hollywood, instead choosing to focus on deeply flawed, deeply realistic characters, allowing his band of actors the space to perform without inhibition.

Of course, these kinds of films were never commercially viable at the box office and so, no matter how acclaimed he became, he was forced to keep financing and distributing them himself. Though Shadows was amazing in that it represented a whole new approach to filmmaking, it was his second independent feature shot ten years later where he really proved himself. Faces (1968), was filmed over three years with a budget of just $275,000. Cassavetes funded it himself with acting paychecks from films like The Killers (1964) and The Dirty Dozen (1967) while also taking out a mortgage on the home he shared with Rowlands. Steven Spielberg famously worked on the set as an unpaid runner. Though the film was entirely independent, filmed in Cassavetes’ house and edited in his garage, it went on to be nominated for three academy awards, including Best Original Screenplay for Cassavetes himself.

1974’s A Woman Under the Influence saw Cassavetes and Rowlands take out another mortgage on their house as well as two Oscar nominations for Best Director and Best Actress respectively. Lead actor Peter Falk loved the script so much he forked over $500,000 of his own money to make up the budget.

Falk and Cassavetes first worked together on Husbands after Cassavetes pitched the idea to Falk at a Lakers game. After securing some funds from an Italian count and roping in Ben Gazzara to play the third lead upon spying him in a parking lot, Cassavetes got to work on what might be one of the most chilling explorations of toxic masculinity ever committed to the screen.

His later films, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976), Opening Night (1977) and Love Streams (1984) called for a similarly scrappy approach and many favours from long term collaborators, and have gone on to inspire directing giants such as Martin Scorsese and Paul Thomas Anderson.

It’s funny, we always hear about the influence of The French New Wave and people like Truffaut and Godard, but Cassavates made Shadows three years before Godard’s Breathless. He was truly pioneering, ripping up the playbook and paving the way for countless filmmakers who would follow him. Today we can see his lasting influence in the work of the Safdie Brothers who named Shadows, Faces, A Woman Under the Influence, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie and Opening Night in their Top 10 films on the Criterion Collection. We also have him to thank for the work of Lars Von Trier and the Dogme 95 Movement, who were inspired by his minimal intervention and character-driven plots. The Celebration (1998), which is often touted as the first film of the Dogme 95 movement, is a gripping, twisted family drama of which Cassavetes would be proud.

The Independent Spirit John Cassavetes Award is presented to up and coming filmmakers each year in acknowledgment of his contributions to independent cinema, a legacy which has prompted many aspiring artists to stop resting on their laurels. It was the experience of seeing Shadows, in fact, that Scorsese credits as his call to action. ‘When I saw Shadows with the camera right in that house giving such a direct communication with the human experience, with conflict and love and all of this, it was as if there was no camera there at all, as if you were living with these people. Once we saw that, we all realised that you can’t sit around and talk about making a film, you gotta just go do it.’

When Cassavetes made that radio show appearance back in 1956, not only did he set the wheels of his own career in motion, but he showed countless people what was possible with a lot of passion and a little bit of nerve.

Written by Leah McDonald