Where to Start with Jean-Luc Godard

Few filmmakers have had quite the impact on cinema as Jean-Luc Godard. Along with fellow filmmakers such as Francois Truffaut and Agnes Varda, Godard spearheaded an entire movement and arguably changed the trajectory of the artform.

The 1960s saw the emergence of the French New Wave, and was Godard’s most famous decade of work. During these years, critics dissatisfied with the current state of cinema decided to make their own films that rejected traditional techniques. These new films favoured the use of real locations and experimental editing, holding more artistic merit than what came before. In contrast to the money-printing Hollywood pictures, the New Wave saw artists prove films could simultaneously entertain and challenge audiences, allowing them to connect to characters and themes on a deeper level. These films were personal and built upon the already existing auteur theory, the idea that a director holds sole authorship over their film.

Godard’s fingerprints can be found throughout his oeuvre with numerous qualities that make his work identifiable and unique. Often credited as disregarding the rulebook, Godard’s editing was initially shocking to people. Typically, cuts were used in film to maintain pace or continuity; editing was kept hidden from an audience. Godard instead drew attention to the editing in his films, introducing a new dimension of filmmaking to moviegoers. Jump cuts intentionally disrupt the flow, sound is manipulated to present the characters’ true feelings, and unusual lighting immerses even the most hardened cinemagoer. His films were demystifying and served as a reminder that we should never have to settle for less.

He was a towering figure in the film world. His persistent attitude and passion for cinema made him a titan – as feared as he was respected. Even his signature look – the sunglasses, tuft of dark hair, slender demeanour – feels like a pastiche character made to represent a typical pretentious director. But, without Godard, that pastiche wouldn’t exist. He was dedicated to the artform; perhaps too dedicated given the fractured relationships often created by his refusal to back down. His closest friend, François Truffaut, became one of his sworn enemies after the release of Day for Night in 1973, Truffaut’s love letter to cinema. Godard walked out on the film, describing it as a lie. The former allies exchanged numerous spiteful letters and never spoke again.

With such an imposing reputation and dozens of films under his belt, getting into Jean-Luc Godard can seem impossible. That’s why, in this edition of Where to Start With…, we at The Film Magazine are presenting multiple avenues that can make that process easier. In honour of his iconic, legendary and ever-influential career, this is Where to Start with Jean-Luc Godard.

1. Breathless (1960)

The most obvious place to start with an oeuvre so beloved and so large would be at the beginning, with Godard’s debut Breathless.

Released in 1960, Breathless was a fresh approach to film that turned other filmmakers’ mistakes into new rules, introducing a new filmic language. Most noteworthy was its unusual use of jump cuts that broke up the traditional narrative often seen in Hollywood movies. These bold editing choices made the film stand out and suddenly opened people’s eyes to how fluid a film’s form could be. Its uniqueness became influential to several generations of filmmakers in the United States, from Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino, and even spawned an American remake in 1983 starring Richard Gere.

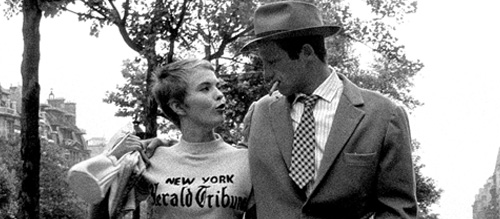

Set on the bustling streets of Paris, Breathless follows the doomed romance of criminal Michel and his American girlfriend Patricia. Michel steals a car and shoots a tailgating police officer, resulting in him spending the rest of the runtime avoiding capture. He turns to Patricia for help and tries to persuade her to escape with him to Italy. This somewhat tired plot is kept alive with the riveting interplay of its two leads and the freeform of the narrative presentation. At no point is the film anything but electric. Breathless is capped off by one of cinema’s most brilliant endings – a shocking yet tragically inevitable one – with its final moments being the perfect blend of realism and French romanticism, something Godard mastered effortlessly.

Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg play characters that belong on the big screen. Equal parts tough and charming, they are the quintessential French New Wave protagonists; the moral ambiguity of the characters is what makes them so compelling. Nothing is black and white in Godard’s film (aside from Raoul Coutard’s stunning cinematography) as he challenges us to side with people we would usually cross the street to avoid. The film made Belmondo a star, and it’s clear to see why from the very first frame. He has the swagger of Humphrey Bogart and the presence of Marlon Brando. His counterpart, Seberg, delivers a nuanced performance of a character torn between right and wrong. Her effortless portrayal led to François Truffaut lauding her as the best actress in Europe.

The natural progression after this film would be to watch Godard’s follow-ups: Une femme est une femme and Bande à part, both continuing the playful spontaneity of Breathless. But it was this first film that really set the world on fire. Breathless, along with other heavy hitters at the time, like Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, became the manifesto of an entire film movement. It’s the rare film that lives up to its legendary reputation, with the spirit of France’s youth pulsating through every line of dialogue and every risky cut.

2. Pierrot le Fou (1965)

Godard’s tenth film feels like a natural step up from his earlier efforts. It is larger in scope and feels like the work of a master who has honed their skill. Like Breathless, Pierrot le Fou is about escape. The Bonnie and Clyde-like story follows Ferdinand and Marianne as they travel from Paris to the Mediterranean Sea. Ferdinand is leaving the mundanity of everyday life, whereas Marianne is on the run from Algerian hitmen.

Their ever-evolving romance is thrilling to watch, as is the dialogue that, if featured in a 2010 romcom, would have been plastered across everyone’s Tumblr feed. “Why do you look so sad?” Ferdinand asks. “Because you speak to me in words and I look at you with feelings,” replies Marianne. Exchanges like this are heartache-inducing and littered throughout the beautiful script. Despite these moments, the film is oddly joyous – there’s a common misconception that European art cinema has to be dull and depressing, but that could not be further from the truth with Pierrot le Fou, which constantly has the fun dial turned up to 11. There’s something so alluring about the free spirit that unifies the characters and story. Even when the darker elements occur, it’s difficult to resist jumping into the frame and enjoying life under Godard’s rule. It’s an inspiring tale, and one that made acclaimed director Chantal Akerman want to make films.

Belmondo returns, now a seasoned professional. He maintains the charm of his Breathless role, but his magnetism has increased tenfold. He brings a jadedness to this character as he escapes a married life, which compliments his newfound freedom. He is nicknamed ‘Pierrot’ by Marianne, from where the film gets its title. Pierrot means sad clown and Belmondo captures that essence perfectly. He can be fun and carefree, but he is ultimately dissatisfied with society, something that haunts his character until the end. Starring opposite him is Anna Karina, in one of her many collaborations with Godard. Karina appeared in eight of his films, becoming his muse and then his wife from 1961 to 1965. Her frequent appearances led to her becoming the poster child of the French New Wave. Every performance from her is stellar, but this might just be her best. She commands each scene and even manages to steal the film away from Belmondo (in a literal sense too as she continuously interrupts his narration).

Godard once again teams up with Raoul Coutard, who this time adds a pop art-influenced gloss over the film, resulting in one of the best-looking films of the 1960s. Godard often said this was a film about France, which is seen in the richness of blues, whites and reds. These colours are accentuated throughout, from the characters’ clothing to props and lighting. The film’s visual DNA is France, making every striking frame carefully calculated. The dominating French imagery is a hint of Godard’s more politically-charged films to come. For that reason, Pierrot le Fou is both a perfect entry point and bridge between phases of Godard’s filmography. It gives you a glimpse of what’s to come and builds on what has already been.

3. Masculin féminin (1966)

Released one year after Pierrot le Fou, Masculin féminin dives further into Godard’s interest in politics. Arguably this is Godard’s most accessible political film – his later efforts may seem alienating to some with subject matter that is difficult to comprehend unless the viewer has prior knowledge. With Masculin féminin, you are able to get an understanding of Godard’s radical side while still enjoying an engaging story.

Godard successfully utilises New Wave icon Jean-Pierre Léaud, a world class actor who carries as much weight in art cinema circles as Liv Ullman and Toshiro Mifune. He is delightful anytime he graces the screen, but to have him team up with Godard makes this a must-see for any cinephile. Here, Léaud shines as the idealistic and naïve Paul who meets the up-and-coming pop star Madeleine (Chantal Goyer). The pair have notable differences when it comes to music taste and political beliefs, but soon become romantically involved and later move in together. The rest of the film explores their differences in a vignette-like style, with Paul growing increasingly agitated by the political landscape and Madeleine more impassioned by her music career. It’s this wrestling of ideals that makes the film so compelling. When Madeleine confesses her love to Paul, he leaves to graffiti anti-De Galle slogans. It is Paul’s conflict that also represents Godard’s own artistry – the idea that films can entertain and also inform. Yet, post Masculin féminin, Godard’s films skewed more on the informative side as he created the Marxist production group, Dziga Vertov. Would Godard also have walked out on someone confessing their love to him? It’s possible. If Paul is truly a vehicle of Godard’s own morals, then Léaud was a very interesting choice considering he also served as Truffaut’s autobiographical character in the Antoine Doinel series of films.

Fans of Wes Anderson’s recent feature, The French Dispatch, will notice similarities between the ‘Revisions of a Manifesto’ segment and Godard’s film. Paul seems like the prototype to Timothée Chalamet’s Zeffirelli, and the films even share a song. Anderson uses political themes to paint a general picture of 1960s France, without taking a political stance, whereas Godard is more specific, refusing to shy away from his opinions. Those who were interested by the ideas introduced by Anderson can expand their appreciation with this film. Even aesthetically, there are some scenes that can be seen as a precursor to Anderson’s style. The complex simplicity of the production design and the overall neatness of shots are sure to have inspired Anderson, who has long been vocal about his love of Godard.

While Masculin féminin is political, it is also perhaps the most pop culture-infused film in Godard’s arsenal. The most referenced line from the film comes in the form of an interluding title card that reads: ‘This film could be called The Children of Marx and Coca-Cola,’ which perfectly summarises the aforementioned duality of the characters. Also referenced are pop culture icons such as James Bond and Bob Dylan. Godard’s finger-on-the-pulse ethic paints a clear picture of the social climate of Paris in 1966, from the disillusioned to the inspired. It is backed by an incredibly catchy soundtrack of contemporary French pop hits that tie the film closer to the decade, allowing it to be enjoyed as a snapshot of a different time.

For a while, Masculin féminin was difficult to find, but thankfully a recent UK Criterion Blu-ray has made the film readily accessible. Following this, La Chinoise, also starring Léaud, would be the perfect follow-up due to its similar themes and deeper exploration of politics.

Godard, like any legacy director, can be intimidating for newcomers. As the king of French counterculture, he was and will remain one of the most discussed filmmakers of all time due to his ongoing influence and prolific workload. The idea of approaching such a rich filmography is quite the task, but this guide provides you with what we believe to be three easy points of entry. After experiencing these three films you can then explore one of cinema’s most radical and true artists; the more you watch, the more you’ll learn about the enigmatic man. Godard’s life was his work and that’s how we’ll remember him. He’ll never truly be gone; his art won’t allow it. Stubborn, even after the end. Oh Godard.