That Kind of Man: What L.A Confidential Taught Me About Masculinity

I was ten years old when I realised I’d never seen a man stick up for a woman before.

It was the opening scene of 1997’s neo-noir L.A. Confidential. Gruff cop Bud White (Russell Crowe) calls in a parole violation from his patrol car as he watches a man shaking his wife by the arms in their living room, screaming in her face.

“You’re like Santa Claus with that list, Bud,” says his partner, Stensland (Graham Beckel). “Except everyone on it’s been naughty.” A moment later, White is on the couple’s front lawn pulling the Christmas decorations off the roof. The man throws his wife away and comes outside to investigate.

“Who in the hell are you?” barks the man.

“The ghost of Christmas past,” says Bud White. “Why don’t you dance with a man for a change?”

White ducks a punch, overcoming the man easily before handcuffing him to the porch railing. Quietly he explains: “If you touch her again, I’ll have you violated on a kiddie-raper beef.” As the woman makes her way out of the house, White gives her money and checks she has a place to go, lifting the Christmas lights he just tore down so she can leave, wishing her “Merry Christmas, ma’am.” He turns and heads off to the station.

I wondered why he did it. Later, we’re told he has “a thing for helping women”.

The year before, my mother had taken me and my younger sister to a women and children’s refuge to escape her abusive partner. After years of making our home a hell, one night he grabbed her by the neck and shook her. My sister, not yet two years old, looked on from her highchair, unflinching. Days later, my mother saved us from the man without Bud White showing up.

Since its release 25 years ago, Curtis Hanson’s L.A. Confidential has been remembered as a brilliantly crafted morality story in which three different codes of honour begin to unspool around three men, all members of the LAPD. But it’s also a film about the kinds of men they are, and the relationship between being made a man and making oneself.

Flashy Jack Vincennes (Kevin Spacey) mooches through the department preoccupied with his role as technical advisor on TV cop show ‘Badge of Honour’ and the status it affords him in Hollywood social circles, which he shores up with contrived but salacious arrests typically involving potheads or homosexuals. Later we learn he’s so shallow that he can’t even remember why he became a cop in the first place.

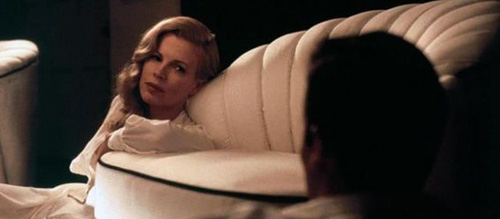

By contrast, Bud White is one of the ‘direct men’ on the force, admired by his colleagues and Captain for his unquestioning “adherence to violence” as much as his hatred of “woman-beaters”. Having become romantically entangled with Lynn Bracken (Kim Basinger), he confides in her the origins of a scar on his shoulder as they lie in bed. Aged twelve, his father went at his mother with a bottle. White “got in the way”.

“So you saved her,” says Bracken.

“Not for long.”

White was tied to a radiator by his father, and watched the man beat his mother to death before being left alone with her body for three days. Despite initial appearances, White is painfully aware that the archetype of the ‘male saviour’ is both brittle and unachievable even if it were a solution to anything. The point is less that he wants to “help women” and more that he is unable to take violence against women any way but personally. It has robbed him too deeply.

White’s opposite, Ed Exley (Guy Pearce), is as ambitious as he is officious, willingly ratting on his colleagues over wrongdoing rather than closing ranks for the sake of camaraderie or rough justice. Exley doesn’t flinch while on brazen political manoeuvres, yet of all the cops in the department he is most reluctant to apply himself physically, at least until he throws himself at Lynn Bracken – a high-class escort who models herself on Veronica Lake – apparently unable to bear the indignity of Bracken’s admission that she is involved with White because of all the ways he is unlike Exley, and because despite appearances White can’t hide the good in himself.

Exley’s sense of entitlement has two aspects: he is a ‘smart man’ on the force – diligent, tenacious, upstanding – and yet he is unable to shake comparisons to his deceased father, a department legend, whose methods Exley deplores. However much Exley wills it, the LAPD is not a meritocracy. And yet, while his own motivations for joining the police stem from the escaped killer who gunned down his father while off-duty, he is unable to shake the perception that his professional successes, especially at his young age, are not unrelated to the esteem in which his father is held, even in death.

This might be the reason White hates Exley so much. How could a pompous, stick-in-the-mud misfit seem to fly so high despite having no truck with the fraternity held so dear by other men in the department? However hard he tries to carve his own path, everything about Exley gives the impression his career owes a debt to the precedent set by his father. Meanwhile, White’s father made him “just the guy they bring in to scare the other guys shitless”. As he begins to suspect all is not what it seems in the homicide case at the centre of the film’s plot, he castigates himself for not being smart enough.

I tried to beat a guy shitless once. I was nine years old and he was a boy at my new school who had decided to bully me for my strange accent. It was futile and short-lived, as all playground scuffles are. But on such occasions, the man in our house had made it clear I was never to return home in tears, as I typically would, to his shame, if I hadn’t first stuck up for myself with my fists. To help me “toughen up” for whatever blows I might receive in return, he would punch my arms and legs so they were numb, to make me a man more like him. A bright pupil in class, I had much more of the Ed Exley about me than was acceptable at home or made me useful in the playground.

Not long after we left for the refuge, my grandmother held me to her chest and told me I was now the “man of the house”. This meant being “big and brave” because my mum and toddler sister would depend on me to “look after them”. No longer a boy, I understood the implication: there was a kind of man I needed to become. Maybe even the kind of man that, with my limited but acute experience of the world, I wanted to be. I’d just never met him.

It is the shared realisation of foul play in the film’s homicide case that forces the central trio to reckon with what sort of men they actually want to be. Exley realises his crowning achievement was accomplished on false pretences that wouldn’t have been amiss on his father’s watch. Vincennes – whose breezy life is possible precisely because of his lack of conviction – develops a conscience upon realising his work has actually earned him respect from others (indeed, from a naive man he has twice endeavoured to set up) that for whatever reason he has seldom shown himself.

Most significantly, White becomes increasingly turned off by the jobs he’s assured he was “born for”. Realising his bellicose demeanour is more a product of nurture than nature, he grapples with the tension between the man he is and the man he wants to be. We see glimpses of the latter in his intimate moments with Lynn Bracken – tender, sensual, soft. Yet after walking into a trap set for him by the film’s shady antagonists, he ends up striking Bracken, believing she has betrayed him, violating his cardinal rule.

The moment hits so hard not only because we know White’s backstory, but because by this point we have, almost imperceptibly, become used to seeing White look as though there are tears forming in his eyes – whilst watching a domestic abuser hit his wife; when he is suspended from duty; each time Bracken divines the man beneath the exterior; when he finds a rape victim, kidnapped and restrained in the house of a suspect. Finally, he breaks: his honest desire for tenderness and care betrayed by his own propensity for violence, which has become an inarguable truth of White’s character. He is ashamed and humiliated by his actions.

Like most women who leave abusive men, my mother went back to her partner a few times before things were broken off for good a few years later. Time and again I wished for a ‘Bud White’ to turn up outside our house looking for a dance. It says something about boyhood that – at the age of eleven or twelve – I would most readily recall White’s origins and methods. Now a man, it is his struggle that resonates most loudly.

There is a well-trodden truism that abusers are often themselves victims of abuse. Indeed, it would be easy to frame White’s assault on Bracken as the actions of a victim-turned-abuser: a classic pattern. But less frequently articulated is the sense of guilt and responsibility carried by boys who have seen for themselves what kind of man they could grow up to be, and have known few others; boys who have been made no stranger to violence long before they are capable of perpetrating it, as they adapt to manhood and eventually have no choice but to reconcile themselves with it in whatever way they can.

In the final scenes of L.A. Confidential, White gets in the way once more – this time for Exley – taking multiple bullets for him. Surviving but temporarily immobilised and unable to speak, White is carried to the film’s end by the relationships he has formed with Bracken and Exley. For all the film’s initial cynicism, it ends with optimism; not that resolution can be achieved so much as reconciliation, in the acceptance that the kinds of men we are – or that others would have us be – can be made and remade still.

Written by Craig Gent

You can support Craig Gent in the following places:

Twitter – @aloneinthefront

Letterboxd – /aloneinthefront

Instagram – @aloneinthefrontrow