Kissing the Devil’s Arse: Witch-Hunting in Eurocult Cinema, c.1968-1976

The Bloody Judge (1970)

One of the pictures most immediately influenced by Witchfinder General, Spanish director Jess Franco’s The Bloody Judge (1970) was made during Franco’s association with producer Harry Alan Towers, and was a co-production involving British (Towers of London Productions), German (Terra-Filmkunst), Spanish (Fénix Cooperativa Cinematográfica) and Italian (Prodimex Film) sources of financing. The film, as originally released, exists in a confusing variety of different edits for different markets – some underscoring the exploitative witch-hunting element, others highlighting the film’s historical focus on the Monmouth Rebellion. (The way the picture is filmed, with Lee’s scenes as Jeffreys seemingly shot at a different time to much of the footage focusing on witch-hunting, one wonders about the extent to which Lee was pitched the film as a more ‘straight’ historical narrative about the Bloody Assizes.) In particular, the film had several very different endings. (Most digital home video releases are composite cuts, combining as much footage from the existing versions of the film as possible, and featuring a denouement that amalgamates several of the available endings.)

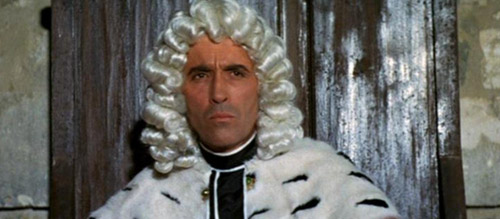

Christopher Lee plays Judge Jeffreys, the notorious ‘Hanging Judge’, who Franco reimagines as a persecutor of heretics. ‘1685. Storm clouds gather over Europe’, a narrator intones over the opening scenes, ‘While the Duke of Monmouth plans to raise an army, invade England and usurp the throne from King James [II], the Lord High Chief Justice Jeffreys dispenses his peculiarly inflexible form of justice to vast numbers of subjects, both real and imaginary. This is the time of plot and counterplot, a time of witchcraft, when the shadow of the executioner blots out the innocent and the guilty alike’. Aside from the use of narration to add credence to the historical tale, Franco also borrows from Reeves’ Witchfinder General a depiction of children as witnesses to, and re-enactors of, adult cruelty: after the opening credits, The Bloody Judge begins with a scene in which young people are shown with an effigy of Jeffreys, a noose around his neck, whilst singing a song in Latin about witchcraft. A man says to a chicken, ‘We shall destroy the bloody church, my dear; and then, all of us shall rejoice’.

Pretty Alicia Grey (Margaret Lee) is accused of witchcraft and thrown into the dungeons, where she is tortured in order to extract a confession. Alicia’s sister Mary (Maria Rohm) becomes a target of Jeffreys when her lover Harry Selton (Hans Hass) is implicated as a participant in the rebellion by the Duke of Monmouth. Harry’s father, Lord Wessex (Leo Genn), thus becomes embroiled in a conflict with Jeffreys that also involves Jeffreys’ sadistic henchman Satchel (Milo Quesada), who is given a wonderful broad Northern accent in the English dub: ‘Fight away, me beauty. We ‘ave the ‘ole night before us’, Satchel grunts as he attempts to rape Mary.

In the scenes featuring Howard Vernon’s sadistic torturer Jack Ketch, named after the notorious executioner associated with Charles II’s reign, Franco’s otherwise staid filmmaking is replaced by something more energised and organic. The alleged witches are shown in dungeons, in various states of undress, being tortured on racks and with hot irons. Here, Franco’s approach to the material overlaps with his WIP (Women in Prison) films of the era, and later, such as Der heisse Tod (99 Women, 1969) and Frauengefängnis (Caged Women/Barbed Wire Dolls, 1976). Certainly, Franco suggests that like Hopkins in Witchfinder General, Jeffreys is taking advantage of the social dislocation caused by a time of dissent (the Monmouth Rebellion) in order to pursue his own curious peccadilloes. When Alicia is brought before Jeffreys for trial as a witch, as the charges are read to the court Franco cuts from Jeffreys to a close-up of Alicia’s bosom; Jeffreys’ subsequent declaration that Alicia must be ‘examined thoroughly for abnormality of mind and body’ thus takes on a more lascivious meaning. ‘This is no time for the faint-hearted’, Jeffreys says, ‘In troubled times we must all search our consciences’. But Jeffreys appears to be troubled by his own conscience, and a number of times Franco presents a montage of images of torture before cutting away to an anxious, sweating Jeffreys. ‘Justice is a terrible thing’, Jeffreys intones, ‘But justice must be done!’ Jeffreys has a wavering belief in his right to pass judgement on others: ‘Sometimes I ask myself whether the right to life or death was ever given to mere men’, he narrates, ‘or if God almighty did not deliver unto me the responsibilities for that which we are doing’. He adds that, ‘I am assured that we were not unjust in dealing the most atrocious punishment to these criminals’. Later, as the film builds towards it climax, Lord Wessex reminds Jeffreys of the violence enacted in Jeffreys’ name at a distance: ‘My lord, would there but once you had seen your own sentences carried out’. When the political tables are inevitably turned, Jeffreys faces his own execution and reflects on his culpability: ‘Surely a man loyal to God, king and country, such as I have always been, cannot be condemned as cruel or unjust for pursuing his duties vigorously’.

Les démons (1973)

Franco’s later witch-hunting film Les démons (1973), made during Franco’s short-lived but extremely productive period of association with producer Robert de Nesle, revisits some of the territory of The Bloody Judge but is more explicit and far less grounded in historical fact. Though Les démons is set in England, again during the period of the Bloody Assizes, the locations and costumes seem far more European, influenced as they are by the iconography of Ken Russell’s The Devils. Franco weaves into the story of Les démons various references to characters from both his previous films and other fictional works. Rosa, the blind witch from The Bloody Judge who acted as mentor to Mary makes a reappearance here as Kiru, an ageing hedge-sitter who lives in the forest, and who helps at different points in the narrative to guide the film’s two female leads, sisters Kathleen (Anne Libert) and Margaret (Britt Nichols), onto their respective paths of supernatural revenge. The character of Jeffreys also reappears here as Grand Inquisitor Jeffries (John Foster), who is allied in his witch-hunting activities with Lady de Winter (Karin Field) and Renfield (Alberto Dalbès) – names from Alexandre Dumas’ “The Three Musketeers” (1844) and Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” (1897), respectively.

Les démons opens with an old hag being given three tests for witchcraft by torturer Truro (Luis Barboo), under the guidance of Jeffreys. Her tongue is checked for spots; she is pricked; and water is poured on her body to see if it evaporates. (As, in making a covenant with the Devil, witches had rejected their baptism, it was believed water would resist contact with them.) She is declared a witch and sentenced to death. Here, Franco pulls the rug from beneath his audience, by having the old hag admit almost proudly to being a witch. ‘It is true! I’m the Devil’s bride!’, she declares before adding, ‘The Devil will take you all! [….] I die by your hands but my daughters will avenge me!’ The hag’s promise of supernatural revenge is enacted by her daughters, Kathleen and Margaret, who were taken into a convent as children and are guided on a path to avenging their dead mother through contact with Kiru, the blind hedge-sitter in the woods. Kathleen and Margaret are also associated with political rebellion: their father is revealed to be Lady de Winter’s husband, Lord Malcolm de Winter (Howard Vernon), a ‘sleeper’ agent of the Duke of Monmouth’s rebellion.

With the exception of Blood on Satan’s Claw, most of Les démons’ predecessors in this particular post-Witchfinder General subgenre resisted any temptation to confirm in an outright manner the existence of the supernatural; in denying any representation of witchcraft as ‘real’, the films invariably threw focus onto the cruel superstitions of the witchfinders and the communities that employed/enabled them. In so doing, the predominantly female targets of the witchfinders are painted as victims. However, in Les démons Franco emphasises the concept of witchcraft as a very real force within the narrative, giving the film’s witches a sense of agency and autonomy. The film’s confirmation of witchcraft as a ‘real’ force follows the persecution of the hag (Kathleen and Margaret’s mother) by Jeffreys, de Winter and Renfield: in other words, the Devil’s agency, and the manner in which his will is enacted through ‘deviant’ women, is motivated/unleashed by the persecution of his servants.

Where much of Franco’s work as a filmmaker engages with female stereotypes and female sexuality, Kathleen and Margaret embody two competing schemas of femininity. Kathleen is accused of not paying attention during morning Mass, and longs to be with nature. ‘It’s like sap rises in me’, Kathleen tells Mother Rosalind (Doris Thomas); and shortly afterwards, Kathleen is seen masturbating in her room. Kathleen is a servant to her desires. Margaret, on the other hand, is focused and chaste. ‘These two girls differ greatly in looks as well as temperament’, Mother Rosalind tells Lady de Winter, ‘Margaret is humble, self-effacing and obedient. Kathleen is pleasant – in fact, very pretty – but I fear her faith is weak’. ‘Could she be a witch?’, Lady de Winter asks. ‘She’s very sensual’, Mother Rosalind responds conservatively, ‘Even provocative’. Against these two young women stand forces of repression which, though commanded by Jeffreys, are corralled by Lady de Winter. Lady de Winter’s role in this film quietly subverts the assumed patriarchal order of most witch-hunting films.

Lady de Winter tests both Kathleen and Margaret for congress with the Devil. Her approach in this endeavour is blunt. ‘Have you ever had sexual relations with the Devil?’, Lady de Winter asks the two sisters before demanding that they bend over so that she can grope them in order to assess their virginity (or otherwise). Whilst doing this, Lady de Winter gives the ‘eye’ to Renfield, who is her illicit lover: the viewer might be reminded of 19th Century satirist Rev Sydney Smith’s assertion that ‘Men whose trade is rat-catching love to catch rats… and the suppressor is gratified by his vice’. Kathleen is soon declared a witch and taken to the dungeons, where she is tortured with clamps on her nipples and hot irons applied to her flesh. ‘Admit it’, Renfield tells Lady de Winter, ‘It excites you’. ‘It’s a lovely sight’, Lady de Winter concedes before falling into a passionate embrace with Renfield. Franco paints witch-hunting and torture as sexual kinks of the privileged; their enactment is for the kicks of powerful aristocrats. The torture of the ‘witch’ Kathleen is here depicted as having the effect of an aphrodisiac on both Lady de Winter and Renfield, underscoring the sadistic sexual pleasure witch-hunters in other films get from torture, which in this stage of Franco’s career is pulled from the subtext and placed centre-stage. Here, Franco makes explicit what was often implied in earlier films about witch-hunting, paving the way for the evolution of Franco’s career into the WIP fetishism of the aforementioned Frauengefängnis and increasingly explicit ‘nunsploitation’ films such as Liebesbriefe einer portugiesischen Nonne (Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun, 1977) – in which a novice nun, Maria (Susan Hemingway), is in effect gaslighted by a convent run by Satanists.

However, expectations are subverted when the innocent Margaret is the first to find her way within the world of witchcraft. Margaret and Kathleen’s supernatural powers are innate, and Mother Rosalind proposes that Margaret be exorcised: ‘It is certain that the blood in your veins contains the seed of this evil curse’, Margaret is told by Mother Rosalind, ‘This seed must be torn out and destroyed’. In her room at the convent, Margaret experiences a vision of her dead mother, the hag tortured and burned in the film’s opening sequence. ‘Your destiny is to follow in my path and avenge me’, the hag commands Margaret, ‘Those who persecute us must be punished for their cruelty’. This vision is all the more effective for how plainly Franco presents it: the hag simply appears in a corner of the room, against a wall, and disappears just as quickly. Subsequently, the Devil appears in the guise of a man, telling Margaret that ‘You and your sister are daughters of a witch. But our enemies didn’t allow you to grow up by her side. Your mother asked me to initiate you, to make you a bride of Satan’. As the Devil initiates Margaret by penetrating her from behind, Franco cuts repeatedly to a shot of a crucifix hanging on the wall behind the couple. The crucifix bears an effigy of Christ, and Franco zooms into the expression on the face of this effigy – which seems to gaze down on the Devil’s coupling with Margaret with a look of shock. It’s a crude moment, vulgar in its ambitions, but as with so many similarly vulgar moments in Franco’s career, it is carried by a sense of irony and enlivened by its audacity.

In Les démons, Franco foregrounds the way in which female sexuality is used as an index of deviance and is also seen as infectious. This is a recurring theme in Franco’s work that is particularly evident in his 1973 film La comtesse noire (Female Vampire/Bare-Breasted Countess), in which Lina Romay’s mute vampire Countess Irina Karlstein essentially fornicates her loves to death. (This aspect of La comtesse noire is made even more overt in the hardcore variant of the film, released in France as Les avaleuses.) After Margaret has coupled with the Devil, Mother Rosalind enters her room and discovers Margaret on her bed, naked. ‘I enjoy being like this’, Margaret says, ‘to see and caress my skin’. Mother Rosalind suggests that Margaret is ‘a creature of Satan too’, and Margaret responds by telling her, ‘It’s true. The Devil spent the night with me’. Margaret then seduces Mother Rosalind, who leaves and, appalled by what she has done, commits suicide by throwing herself from a balcony onto the central courtyard of the convent.

Recommended for you: Loincloths, Muscles, Sorcery and the Rock of Uranus: A Journey Into the Realm of the Italian Peplum (c.1958-1965)

Margaret pursues her mother’s quest for supernatural revenge incessantly, whilst Kathleen – who was initially considered the least ‘pure’ of the sisters – is freed by Lord de Winter and flees across the countryside. Eventually, Kathleen is caught by Renfield, who quickly falls in love with her. Lady de Winter and Jeffries are angered by Renfield’s betrayal, capturing and torturing him too. However, Jeffreys promises Kathleen that he will let Renfield go: ‘But first, make me your victim, beautiful witch’, Jeffreys demands, ‘Prove to me that witches weren’t only made to be hated’.

As the film builds towards its climax, Margaret reappears and demonstrates the depth of the supernatural powers that she has acquired. She is able to transform anyone who kisses her into a bleached skeleton. Her first victim is Lady de Winter; Lady de Winter seduces Margaret after a banquet, unaware that her new lover is one of the sisters she has been pursuing throughout the film. ‘And now you will die’, Margaret tells Lady de Winter, ‘I’m a real witch and all who take pleasure with me must die!’ As the Duke of Monmouth’s rebels advance and storm the castle, Margaret, Kathleen and Renfield are freed. However, when Kathleen witnesses Margaret using her power to turn Renfield into a skeleton, Kathleen turns her sister over to a baying mob. Margaret is subjected by Jeffreys to the same three tests as her mother was in the opening sequence, and like her mother Margaret is sentenced to be burnt to death. However, as she is about to be burnt, Margaret asks for a kiss of forgiveness from Jeffreys; her request seems deliberately similar to Grandier’s request for a kiss from Father Barre during the climactic execution in The Devils. (In The Devils, this kiss is given by Father Mignon, who is then mocked by the crowd as a Judas.) Jeffreys, of course, is turned into a hideous skeleton. ‘All of you, my tormentors, will also die’, Margaret promises the gathered crowd, ‘I curse all of you! My vengeance will be terrible. A devastating vengeance from the world beyond’. Margaret is incinerated, and in the film’s final moments Franco shows us Kathleen, who has ventured into the woods, encountering the blind hedge-sitter that lives in the cottage there…

There is a satisfyingly cyclical nature to the structure of Les démons – the hag’s torment in the opening sequence mirrored by her daughter Margaret’s torture and execution in the final moments. The hag’s vengeance is enacted within the supernatural powers of Margaret, and Margaret’s promise of revenge seems destined to be pursued subsequent to Kathleen’s encounter with Kiru, the hedge-sitter in the woods. Though Franco’s vision is restrained by obvious limitations in terms of resources, there is a delirium – a feverishness – in Les démons’ examination of the processes and politics (both traditional and sexual) of witch-hunting.