Katie Doyle’s “Movies I had a Religious/Spiritual Experience With” Part 5: The Exorcist

For any regular reader of The Film Magazine and of this “Movies I had a Religious/Spiritual Experience With” series of articles in particular, you will know the drill by now – Spoiler Alert! – but I would this time also like to make a disclaimer that these articles are based on my own personal opinions which arise from my own life experiences as a Roman Catholic. Additionally, in no way am I claiming that the experiences I discuss are unique to the Catholic faith, but as a personal piece I believe it is not my place to speak for other faiths I have no experience in.

“Hocus Pocus!? Hocus Pocus, indeed! Don’t you know those words are a deliberate perversion of the Latin Mass, in fact a mockery of the very moment of blessing: Hoc est corpus meum – This is my body!”

“Oh. I didn’t.”

“Bet you also didn’t know that Jack in the Boxes were made to poke fun at tabernacles, did you?”

“No, you’re right.”

Religion is a funny thing, even for the faithful. For some of us, we didn’t have much of a say in the initial part of our subscription. As soon as those drops of Holy Water touched our foreheads, all the way back when we were mere weeks old, we have been sealed with the mark of Catholicism. A brand, you could say, would stay with a person forever, no matter how far that person may stray into different philosophies. As a catholic, I regularly think: does this branding affect the way the world perceives me?

Well, the above tidbits are examples of the English Reformation’s agenda to belittle and vilify Catholic culture, which indeed succeeded for a century or so. But the times changed, the variety of people that made up the face of the nation transformed – words and toys lost their original stinging bite, becoming mere curiosities of the culture of the English-speaking world. I can’t seriously claim the English Reformation of 1517 that spread through Britain has hurt me as an individual – not like the brutal religious discrimination seen elsewhere in the world. Of course, there are murmurs of ancestors from the likes of Belfast fleeing from persecution, but just like the vilification tactics of The Reformation, as soon as my ancestors set foot in England, the bloodline slowly but surely Anglicised right until the pain of the past became a half-forgotten memory.

What I do find curious though, is the way that Catholicism is viewed in the relatively Bible-bashing nation of the USA. In their more evangelical, charismatic circles, Catholicism is viewed as just one step away from out and out devil worshipping. All I’ll say is that it is no mere consequence that the image of the inverted cross is largely associated with demonic activities in pop-culture, despite the fact it’s actually a symbol of the papacy owing to how St. Peter was crucified upside-down. Still, this is no real cause of grief for me, all the way up in the North-East of England, but it’s still pretty interesting to see in what ways my religion intersects with Hollywood. However, just like the subject of this essay, it’s not threats from the outside we should be worried about – crisis of faith is very much an internal struggle.

These truly are dark times we are living through; often people of faith can turn to their religion during times of strife, but with the reduction in church services in 2020, including the cancellation of all formal Easter celebration services throughout the Christian world, it feels like even Christ himself has remained dead within his stone cold tomb. As such, in this year in which I have effectively been cast asunder from the tangible presence of God, I have doubted any substantial spiritual experience. And yet I find myself saying words I don’t think I have truly meant until now: inspiration has come from the most unexpected of places – the 1973 horror film, The Exorcist. God really does work in mysterious ways.

It was only intended as a festive watch. The last time I had had any extensive viewing of The Exorcist was all the way back in the first year of university (we had only watched the spooky possession moments). The night had ended with a housemate hiding under my bed and grabbing my leg in the pitch black. Obviously, I avoided the film like the plague after that. With its long-standing reputation of as one of the scariest films of all time, I was no stranger to the basic concept of the film, what with all the parodies, memes and homages that have circulated in the last fifty years. Projectile vomiting! Head-spinning! Spider walking! All of this alongside the well-documented claims of sacrilege. It was enough for me to dismiss The Exorcist as true to the machinations of the English Reformation. I had assumed and resented the supposed depiction of Catholicism as a medieval, decrepit institution in cahoots with all things demonic and out of touch from modern society. Oh, how wrong I was!

The Exorcist‘s depiction of Catholicism instead proves to be rich and nuanced, even comparable to real life, which very much reveals the writer’s (William Peter Blatty) intensely devout Catholic upbringing. The film proves to be the representation I didn’t know I needed, which is what I saw in the character of Father Damien Karras.

One of my greatest personal frustrations with modern Catholic life is the assumption that I’m some sort of anti-intellect luddite, which I’m usually more than happy to debunk with my Masters’ in Chemistry. Unfortunately, the fact of the matter is that a small group of overly outspoken, climate-change denying, evolution-trashing evangelical types have caused the whole of Christianity to be tarred with the same anti-science brush. The Catholic Church’s actual relationship with science is miles away from this common misconception, with it instead having a huge role in the development of The Scientific Method and The Laws of Evidence which are still used today; even some huge scientific discoveries in the fields of genetics and astrophysics can be attributed to Catholic clergy. Damien Karras is no stranger to this set-up; not only is he a priest, but The Church has also paid for him to be trained as a psychiatrist so that he can deliver pastoral care to parishioners and fellow priests. See, none of that faith-healing bollocks approach to mental illness! In fact, Karras even laughs at Chris McNeil’s plea for an exorcism: for him, demonic possession was the biblical answer to ailments people were unable to understand at the time, all the way from epilepsy to schizophrenia. However, like any man of science, Karras willingly sets aside the current theory when presented with new and troubling evidence.

Karras’ first encounter with the possessed Regan is allegorical to the intersection of religion and science for those such as the Catholic faithful. As I made clear before, the Catholic Church is no stranger to modern scientific developments which can be seen in Pope Francis’ essay “Laudato Si”, in which he declared that the destruction of the environment is a sin (very much in keeping with the thinking regarding climate change). However, amongst this scientific reasoning, The Church still partakes in a lot of heavy-lifting in all things ethereal, which means a fair few paradoxes to get your head around: the simultaneously divine and human nature of Jesus Christ; the transubstantiation of bread and wine to Christ’s body and blood despite no noticeable physical change; and of course, reality defying miracles.

Most contemporary Catholics will of course put their “faith” in the wisdom of current medical experts, whilst there is also the religious expectation to accept miracle recoveries (the stuff of pilgrimages to Lourdes and saints’ canonisations). But in this thoroughly modern world, it’s not too shocking that many Catholics, including the clergy, regard the supposedly supernatural with a healthy dose of cynicism – after all, the human psyche is not exactly the best at comprehending paradoxes. So just on cue, Karras first approaches The Devil with a curious and almost cheeky smile, asking it to undo Regan’s straps itself. He only requests the exorcism when he is faced with the utterly impossible in terms of his psychiatric, nay scientific understanding. Even from this point onwards, Karras is still not completely convinced, especially as he tries to apply logical reasoning to the possession. But it is in the defying of the forces and laws of physics that define this tangible existence; we alongside Karras discover the worth of faith.

Why is it that myself and Karras bother to attempt to simultaneously act according to the often opposite demands of the natural and supernatural when it seems practically impossible? In the case of science, it is because it is a matter of duty. Science represents the natural truth of the universe and, as a Catholic, I am obligated to uphold the truth. It is made very clear in the Gospels that to be a disciple of Christ, you must become a servant to humankind. In the context of modern society, supporting modern scientific discovery is on par with upholding the truth for the servitude of mankind: how many examples have there been in recent years in which greedy individuals have denied science such as climate change for their own selfish gain at the cost of the suffering of the most vulnerable in society, such as the most impoverished? However, Catholics’ relationship with the supernatural is harder to explain, and there are many mind-bending concepts that are required to be accepted – the focal point of the religion itself is the resurrection of Jesus from the dead. This is where the idea of faith comes in: ignoring Jesus’ extraordinary story and the documentation of miracles throughout human history, the fact of the matter is that we live a life we don’t have full control over, and many awful things happen to people (often good people) for no apparent reason. As a Catholic I need to be able to understand that amongst the suffering and pain, God’s ultimate plan lies within. I will freely admit in my human pride (which is technically a sin) part of myself rejects this idea. A lot of anguish people suffer is undeniably caused by the action of other people, which falls under the concept of “free will”; so how can God be in control of a universe in which free will exists? Or is it that God orchestrates this misery? If so, then screw this reality. It’s kind of ironic when people claim that religion is a comfort for the weak-minded in the harshness of real life, but for many Catholics, we walk through a world in which the God we believe in seems to have gone missing.

Damien Karras is indeed a fellow Catholic that walks through a world in which it seems God has left. Although an intelligent man of science, logicism has only gone so far in helping him in recognise his purpose in this world.

“I think I’ve lost my faith, Tom.”

Within The Exorcist, Karras is at a point where he believes his psychiatric training can now only go so far in his ministry work. There are too many factors beyond the psychological for him to truly help his patients: issues of vocation, faith and the meaning of life itself. Unwittingly, he has projected onto his patients his own struggles with life. When we find Damien, he is at a crossroads. The film gives us the impression that he has been a priest for some time now, but not only is he now tired of his work as a psychiatrist but also of the priesthood itself. It’s not made clear why Damien became a priest exactly (although a childhood rich in Catholic influence is usually a must in these situations), but we do know what he left behind: a career as a boxer (and a good one to boot) and an infirmed mother. It can’t be mistaken that Damien loves his mother – at the beginning of the film he’s in a state over having to leave her all by herself in her house back in New York, and he fusses over her at the rare opportunity he has. She doesn’t complain of course, and is simply full of love and pride for her son. Again, we can see Damien openly reciprocating this love but there is a definite undercurrent that one of Karras’ motivations to follow a vocation into the priesthood was to run away from his mother and what she represents – an upbringing in poverty and squalor. A vocation in the Jesuit Order instead represents a life of practical glamour in comparison with its opportunities in higher education and fulfilling careers. So when Damien’s mother is admitted to a poorly-funded publicly ran asylum to soon die afterwards, he is consumed with guilt: he believes in his heart that he killed her by abandoning her.

All of this compounds Damien’s self-belief that he is an unworthy man – cursed in the sight of God. In his head, neither his ministry as a priest or his work as a psychiatrist seemed to do any good. And whilst he is occupied with this supposedly meaningless work, his mother is alone and in pain; and then whilst he is consumed by this guilt, he finds he has little time for other people in need – in fact, throughout the film you see him be physically repulsed by the squalor of the homeless and the sickness of the mentally ill. In all levels of life, he sees himself failing. It is also worth mentioning that there is a queer subtext surrounding the character of Damien Karras (which deserves a whole essay unto itself) and it goes without saying that in the context of 1970s America, this would be an additional source of inner turmoil in Karras’ life.

In all of this, The Exorcist gives us cinema’s the most accurate portrayal of a Catholic free from papist and other offensive cultural stereotypes. Karras’ apparent burnout is very much due to his Catholic upbringing, which instills the vocation to help those in need, and despite staying true to this moral code his efforts have come to naught, leaving him with his characteristic sense of worthlessness. Recently, I would imagine that many of us are feeling that our own honest efforts to help people have amounted to nothing, leading to moments of deep despair; and it is during these low points that it becomes harder and harder to dip into the dwindling reserves of our Inner Grace so as to help those in need. Even though such omissions of kindness are usually for the sake of our own survival, it is still very easy to go on and tear ourselves apart over these inactions. The sense of duty and obligation governed by these moral codes professed to us from a young age never switches off – the oh-so legendary Catholic Guilt that regularly rears its ugly head in the form of painful pangs to our conscience.

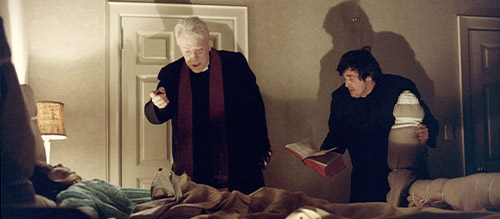

After what has been a lot of deep introspection in trying to understand why the portrayal of Father Damien Karras moved me so much, I now have the rather odd announcement to make: that despite its reputation as one of the scariest films of all time, I found the whole experience to be incredibly life-affirming. I know that out of the thousands who have seen The Exorcist over the years, I am not alone in being able to relate to Jason Miller’s Karras and to receive the gift of hope. For many of us, we have felt that our deeply held belief systems have failed us at some point in our lives, but unknown to us they often are critical in helping us to carry on. Despite Karras’ own doubts and personal demons, he is still resolute in trying to do the right thing (in organising the exorcism of Regan McNeil), even with his begrudging and confused attitude. In the chaos of the actual exorcism it could be argued that Karras was useless and superfluous to the whole process: frightened beyond his wits and relying totally on Father Merrin’s guidance. However, as is often the case in life when the Grace of God seems completely absent, we are struck by a lightning bolt of divine strength. Despite his shortcomings and very human failings, Father Damien Karras is very much the hero of the story, as he makes the ultimate Christ-like sacrifice by offering up his own life to save Regan.

For everyone out there (and not just those of the Catholic faith), The Exorcist is the story of the indomitable nature of the human spirit. Even when our faith or belief system seems to be lacking, if we still stay true to what we know is righteous, we are in fact very much capable of bringing justice to this often unfair world; and is that not a greater feat? That we can be a source of kindness to others when our hearts are empty (especially during great times of sorrow) as opposed to the easy generosity of a worry-free existence?

Part 1: The Prince of Egypt, 2001: A Space Odyssey & A Matter of Life and Death

Part 2: Blade Runner, Cloud Atlas & It’s a Wonderful Life

Part 3: Brazil & In Bruges

Part 4: Beckett & A Man for All Seasons

For the entire back catalogue of Katie Doyle’s “Movies I had a Religious/Spiritual Experience With” series, please visit this page.