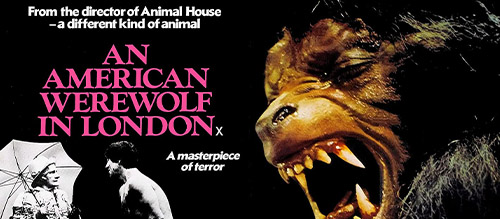

An American Werewolf In London – Unfinished Game-Changing Fun

This article was written exclusively for The Film Magazine by Sarah Williams.

Jerry Mulligan is an exuberant American expatriate in Paris trying to make a reputation as a painter. His friend Adam is a struggling concert pianist who’s a long time associate of a famous French singer, Henri Baurel. A lonely society woman, Milo Roberts, takes Jerry under her wing and supports him, but is interested in more than his art. It’s MGM’s Technicolour musical‒ oh, sorry that’s An American Paris.

This is about An American Werewolf in London.

John Landis’ cult classic about two tourists attacked by a werewolf unknown to the locals has been a scary staple of many childhoods. The transformation sequence is often recounted as the scene that caused nightmares as a kid, and for good reason. It’s always funny that a lot of others watched the film so young, as the sex montage is certainly awkward to view with family. Despite this, horror-comedy is often the best way to ease into horror, as scares are balanced with laughs that ease the tension that could overwhelm younger viewers. As a prime example of this sub-genre, An American Werewolf in London illustrates how harder genre fare can be fun without cheapening the scares, and that’s why it has kept its relevance.

I remember watching the film with my father as a tween when he decided I was old enough for many of his favorite films. Blade Runner I loved, Die Hard not so much. An American Werewolf in London lies more on the positive side, shrouded in a bubble of nostalgia. It was one of my first experiences with horror, but was much easier to sleep after than The Shining, Alien and The Thing, though notably I’ve never felt the sheer panic that is induced in many by the genre at the start. To me, watching it was one of the high points in a messy family relationship, and I often find it hard to be objective because of it.

It’s the dawn of the horror comedy’s rise, and it’s a damn good entry. A British humor predecessor to New Zealander Taika Waititi’s What We Do in the Shadows, with the jokes still landing every time. It’s endlessly quotable – “A naked American man stole my balloons” – and always brings joy. The Londoner comedy is dark satire even without the horror parts of the film, an entry in the early indie canon with the cult classic dark humor of Life of Brian at times, focusing on the physical humor as much as the verbal.

It’s ironic that I’ve always thought of it as a fun movie, considering the story.

David (David Naughton) and Jack (Griffin Dunne) are backpacking when they are attacked by a werewolf. Jack dies from his injuries, and David contemplates suicide due to what he becomes increasingly aware of being a werewolf bite. He fears the change, alone and knowing what is coming for him. The inevitability of the change is what’s so scary, because there’s no way to avoid becoming a monster while remaining alive.

As a film often considered an introduction to horror, it’s psychologically very dark. It goes to show how comedy is able to soften some truly scary aspects, perhaps the thesis of the idea of genre-bending.

A masterclass in paranoia, An American Werewolf in London encapsulates that feeling of being in a strange place on your own with no one to reach out to. With Jack gone, no one believes David about the beast among them. It’s that small-town insular moment, one where the only truth that can be believed is the one spoken by an insider. This is very well done to illustrate isolation – no matter who the two men speak to, no one believes them.

It’s a boy who cried wolf story with a real werewolf, except here it’s the werewolf who cried werewolf.

Trust is flipped on its head, as here the evil supernatural is trying to do the right thing, and we root for him because we knew him before the bite. Once bitten, and twice called a liar, even the werewolf can’t convince the world of his existence.

An American Werewolf in London’s infamous transformation scene holds up well. The film’s gore, wounds and werewolf fur are beautifully done practical effects that only add to the fear factor. It’s gruesome because of how much David does not want this, and the body horror brings his pain to life. Perhaps this scene is so scary to many when they’re young because the characters get exactly what they feared – it’s the cruel justice of the scenario that makes blood run cold, not just the brilliant makeup job.

It’s interesting to think about the representation of a foreigner in a strange place. Perhaps a metaphor for how patriotism isolates outsiders, the transformation of David into a supernatural monster puts him as an enemy of the country he is visiting. By showing an American in Britain, there is no language barrier, and very little by means of a culture barrier. This nationalist alienation then makes the metaphor solely based on the axis of nationality – there is no intersectionality to what David experiences, his werewolf-dom and alienation are purely because of the country he lives in. This may broaden the story, but perhaps the universality is good. It does, however, mean that the social messaging is fairly weak by today’s standards. We get little as to why David is wrapped up in a nationalistic fear even before his werewolf status is known.

Overall, it’s a supernatural dark comedy romp chocked full of British humor. American Werewolf has endured because it doesn’t quite fit in a box. It’s a bit uneven tonally, but it’s one of the original exercises in genre-bending that has actually endured. The film is one that lends itself to repertory screenings at Midnight, with a packed theater of all ages. It’s the kind of movie that’s meant to have quotes yelled as they come on screen, it’s a crowd movie meant to go between multiple generations, just as Monty Python has done.

Roger Ebert claimed the film seemed unfinished, and he’s not wrong, but what’s there is a lot of fun. The blend of genres does feel like two movies with a love story stuffed in, but the two movies on their own are each quite good.

Written by Sarah Williams

You can support Sarah Williams in the following places:

Twitter – @peppermintsodas