A Manchester Legend Immortalised in Black and White: A Reflection on Control’s Portrayal of Ian Curtis

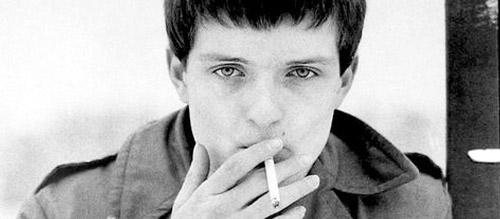

Ian Curtis does not exist in colour; he exists in the grainy, monochromatic photographs of Anton Corbijn. Atmospheric images in which his dark, neatly pressed clothes and short black hair stand out on a background of bright whites and soft greys. His young and stoic face engulfed in a plume of smoke, rising from an ever-present cigarette held gently in his fingertips.

Ian Curtis as photographed by Anton Corbijn.

Control’s director Anton Corbijn photographed Curtis and the rest of Joy Division while they were rising to fame in the late ’70s. His black and white images contributed fundamentally to the band’s gloomy, melancholic image and recognisable aesthetic. Corbijn opts for the same style in his 2007 film Control, the biopic of the late Ian Curtis’ life. The film’s grainy, monochromatic colour palette is so reminiscent of those iconic photographs that it is often hard to tell where lead actor Sam Riley ends, and the memory of Ian Curtis begins.

Based on Deborah Curtis’ (Samantha Morton) biography “Touching from a Distance”, the film follows the last few years of Ian Curtis’ short life. Most notable for fronting the iconic post-punk band Joy Division and tragically committing suicide at the young age of twenty-three, Ian Curtis is a renowned Manchester legend whose legacy plays an essential part in the city’s rich music history. Fans tend to romanticise the life of the shy and awkward young man who infamously penned the desolate and anguished lyrics of songs such as “Isolation”, “She’s Lost Control” and “Love Will Tear Us Apart”. The challenge facing Corbijn and screenwriter Mark Greenhalgh was to tell his story without glorifying his suffering or martyring his death – a trap many music biopics often fall into.

Cinematic biographies often outline the cause and effect relationship between fame and depression, taking us simplistically from point A to point B without digging any deeper into the psyches of the individuals consumed in the erratic trappings of celebrity. Control’s great virtue is its efforts to capture the genuine struggles and conflicting worlds at the centre of Ian Curtis’ life. It pulls no punches as it delves into his relationships, health troubles and marital affairs. By focusing the story on Curtis’ life outside of Joy Division, Corbijn is able to present Ian Curtis as a fully conceptualised and complex human being, rather than the one-dimensional, mythic figure legend portrays him to be.

The film paints Ian Curtis as a dreamer and a romanticist, deeply in love with music, novels and poetry. In its opening scenes, we see his desire to consume as much music and poetry as possible in order to escape his cramped Macclesfield bedroom. When we meet him for the first time, he is applying eyeliner while listening to David Bowie, seemingly experimenting with the androgyny Bowie was so famed for. Later on, after seeing The Sex Pistols destroy the known rules of modern music, we see Curtis walk into his job with the word ‘hate’ tippexed onto his black jacket, fully embracing the punk ideology. This experimentation with image and personality outlines a man desperate to figure out who he is and what it is he has to say.

Control firmly establishes the duality of Curtis’ life and the two worlds pulling him in opposite directions. On one side are his wife and family who need stability and presence, and on the other is the overwhelming success in the music industry and the wild lifestyle of a famous rockstar. The two worlds exist in direct opposition to each other, relentlessly tugging him back and forth while demanding time, money and sacrifice. Of course, they are worlds of his own creation, born from his compulsion to make quick and rash decisions he is not prepared to handle. ‘Let’s get married’ he says at the young age of nineteen, ‘let’s have a baby’ he chirps excitedly a short while later, despite his lack of money and stability.

Yet, while attempting to build a quiet life in his hometown of Macclesfield, Curtis was also establishing himself as a tenacious frontman and songwriter in the band Joy Division; a role which would spiral out of control and uproot him from his sensible nuclear family. Heavily influenced by punk, Curtis, alongside Peter Hook, Bernard Sumner and Stephen Morris, developed a distinctive sound which would establish them as recognisable pioneers in the post-punk movement. Curtis transforms on stage, the quiet and studious man the film outlines in its opening scenes evolves into a deranged spectacle of elbows and half-crazed movements. Lost in the euphoria of his own music, his eyes slip away into delirium and his body spasms eccentrically – he appears high on the experience of performing. We see him attempt to have it all for a while, juggling the roles of husband, father and frontman, before he realises, as dreamers often do, that his choices come with responsibilities he is unable to cope with.

The epilepsy that will come to plague Curtis and rob him of control over his body and mind is foreshadowed early on in the movie. While working in Macclesfield Job Centre, he witnesses a young epileptic woman fall to the ground mid seizure, her frantic shaking reminiscent of the erratic dance moves the singer will later become synonymous with. We see him dull when he begins to suffer from the same condition himself. Not only is the mounting pressure of his work and home life weighing down on his young shoulders, but he must now also live in fear of the uncontrollable fits threatening to rob him of his dignity, career and life. The seizures we see on screen are shockingly violent and frightening, making the illness seem exceptionally cruel given his young age and budding talent. We watch helplessly as the side-effects of his medication slowly descend on him, drowsiness and exhaustion slowly robbing him of all the enjoyment he finds in life.

Things start to come to a head after Curtis starts up an affair with Belgian journalist Annik Honore (Alexandra Maria Lara). When she asks what his home life is like he says bluntly, ‘It’s grey, miserable, I’ve wanted to escape it all my life’. It’s clear Deborah and Macclesfield have become symbolic of Curtis’ feelings of disconnect and oppression. His understanding of their failing relationship was perhaps best summarised in Joy Division’s famous song “Love Will Tear Us Apart” – “When routine bites hard and ambitions are low, and resentment rides high, but emotions won’t grow”. Eventually, Curtis also begins to lose his enthusiasm for performance, which we hear him try to communicate in desperate and fragmented voice-overs. He describes how he feels like a stranger in his own skin, with no control or no idea what to do. The voice-overs come to represent Curtis’ unspoken thoughts, impossible for an audience to ignore but invisible to the friends and family surrounding him. Sam Riley performs Curtis’ psychological torment with subtle and unspoken pain. He morphs Curtis from a bright spark filled with awe to a frightened young man so disappointed with marriage, fame and his behaviour, that he is unable to cope or be alone with himself.

Control stands out from the formulaic genre of music biopics not only because of its authentic portrayal of the renowned singer-songwriter but also because of its spot-on representation of a typical Mancunian. Mancunians communicate through smart-arse sarcasm, often using humour to express anger, pain, happiness and sympathy. ‘I need a cig’ Curtis gasps after witnessing the birth of his daughter. When he suffers a brutal epileptic fit on stage, he wearily asks his manager how bad it was. ‘Chin up, it could be worse. You could be the lead singer in The Fall’ is Rob Gretton’s (Tony Kebbell) tender response. Control’s pitch-perfect script does Manchester proud and elevates Ian Curtis out of the ‘gloomy musician’ role he is most associated with. The lively dialogue paints Curtis as a funny Northern lad who, despite his troubles, was also eager to laugh and enjoy life.

The combination of epilepsy and depression was too much to handle for the talented young singer, and on the 18th of May 1980 he took his own life in his Barton Street home. The hard truth of Ian Curtis’ story is its continued relevance in today’s society, given that suicide is still the leading cause of death in men under the age of forty-five. If we learn anything from Curtis’ short life, it should be to encourage the young men in our lives to express themselves and speak of their struggles openly.

Ian Curtis was a rare soul who will forever be a part of Manchester’s cultural legacy. The city remembers him fondly for his sombre music which continues to touch countless people’s hearts.

Written by Leoni Horton

You can support Leoni in the following places:

Twitter: @inoelshikari

Blog: Leoni Horton Movies