Examining Controversial Depictions of Jesus Christ in Cinema

The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

Researching the anger caused by Martin Scorsese’s first religious cinematic piece really does make one despair.

I ask, in all seriousness; what is wrong with people?

The Last Temptation of Christ does share similar public reactions as the other films featured in this article, such as national bans and censors in the likes of Bulgaria, Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Singapore and The Philippines, and was dropped by its original studio just like Monty Python’s Life of Brian.

However, in the case of The Last Temptation of Christ, the response seems that much more… extreme.

Along with condemnation by several religious groups and leaders upon its release, the LA Times even reported that the spokesperson for Mother Teresa of Calcutta (now St Teresa of Calcutta) had advised Catholics of America that if they intensified their prayers, “Our Blessed Mother [Mary] will see that this film is removed from your land”.

It wasn’t just the case of people protesting outside of cinemas either.

Big name cinema chains actually refused to show the film at all. This was noticed in turn by the big name studios, and Willem Dafoe (who starred as Jesus Christ), was dropped from potential casting for Tombstone.

However, what truly sets apart the public reaction to The Last Temptation of Christ was the shocking violence.

For months after its initial release, Scorsese had to be accompanied by body guards during any public appearance due to several threats he had received from numerous religious groups. Most heinous of all, a group of French Fundamentalist Catholics set fire to cinemas during showings of the film in different cities, including Paris, causing several serious injuries and, sadly, one death.

So, what on Earth happened in this movie?

Why did it drive people to arson and for prominent nuns to call down divine chastisement?

In short, The Last Temptation of Christ is branded as heretical.

But why exactly? And; how did it provoke such shameful violence? Is the church being mocked? Is Jesus Christ portrayed as some sort of grotesque villain?

Well, no. Not really.

To make sense of the film’s apparent heresy, we need to dig deep into the theology.

The Last Temptation of Christ isn’t actually based on The Gospels but on a book of the same name by Nickos Kazantzakis – for his efforts he was excommunicated from the Greek Orthodox Church and was refused burial in his homeland.

Kazantzakis was often at odds with his Mother Greek Orthodox Church – his exploration of different philosophies and religions such as Buddhism led him to openly question Christianity. But, during his journey of spiritual discernment which included disappointments such as the failure of Marxism, he often found that the paths laid out before him led him back to Christ. As such, there is a strong biblical influence in this piece of literature, with the themes of the book being easily summarised by St Paul’s words in his letter to the Hebrews: “For we do no have a high priest who is unable to sympathise with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin.”

The shock and disgust caused by both the book and film is because both Kazantzakis and Scorsese dared to explore Jesus’ humanity – an act of heresy that both men confessed led them to know Jesus better : “I never followed Christ’s blood journey to Golgotha with such terror, I never relived his Life and Passion with such intensity, understanding and love as during the days and nights I wrote “The Last Temptation of Christ”.”

The issue people have with this film is its interpretation of the duality of Jesus’ nature.

One of the most important tenets of most of the denominations of Christianity is that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and is therefore both fully human and fully divine.

Even though this has been repeated enough to millions of Christians over the centuries, in reality it is a concept that is impossible for any person to truly comprehend.

Despite this, any expansive questioning on the concept has led to damning condemnations of heresy: St Nicholas (a.k.a. Santa Claus) famously struck Arius of Egypt after he claimed that Jesus being the Son of God was not equal to God the Father. It is this heresy that Temptation screenwriter Paul Schrader, as reported by The Solute in The Scorsese Experience: The Last Temptation of Christ, Part One, explains lies at heart of the film’s controversy:

“The two major heresies which emerged in the Early Christian Church were the Arian heresy (who got battered by Santa), which essentially said that Jesus was a man who pretended to be God; and the other was the Docetan, which said that Jesus really was God, who, like a very clever actor, pretended to be a man. So, they called a council and branded both philosophies as heresies; but in fact the church has tended to go on its merry Docetan way… The Last Temptation may err on the side of Arianism, but it does little to counteract the 2000 years of erring on the other side, and it was pleasant to see this debate from the Early Church splashed all over the front pages.”

I find myself agreeing with Schrader (made obvious by the tear tracks I find on my face after a viewing), in the sense that Christianity as we know it doesn’t present the most humanised image of Jesus.

The Gospels themselves are surprisingly bare with regards to Jesus’ life as most of their focus concentrates on Jesus’ ministry, which only covers the last 3 years of His mortal life, with only brief mentions of his birth and childhood; and, of course as the Gospels’ intentions was to convert entire nations, their is an extra emphasis on his divinity so as to prove that he is The Messiah – The Son of God. This emphasis is evident with the portrayal of Jesus’ supernatural side, extensively documenting his miracles, omniscience, his power to read a person’s heart, and, of course, rising from the dead.

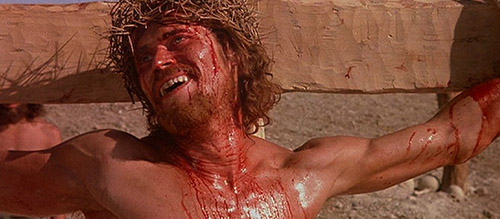

Christ’s most human moments are during His Passion, as he endures the ultimate human experience: pain, suffering and death.

He may not share in our sin and fallibility but the Gospels meticulously document that in the last hours of his mortal life he certainly shared in our fear, vulnerability and physical weakness, and it is Christ’s most memorable moments of humanity which are paramount to the story which the Evangelists proclaim as The Good News. Watching Scorsese’s adaption of Kazantzakis’ work, I cannot and will not agree with the criticism that it refutes the central message of The Gospels, but in its exploration of Jesus’ humanity the meaning of His Passion reaches a whole new level of awe and poignancy.

Many who have watched the film, including myself and many other Christians, found it to be a moving experience.

However, it would still be incredibly naive of me to conclude that there is no cause for offence in The Last Temptation of Christ.

Both the book and film have a disclaimer that they are not biographies, nor are they based on The Gospels, but the film most definitely follows a recognisable approximation of Jesus’ life which would be recognisable to the majority of any audience. Those squinting at recognition would then be shocked by the inverted portrayals of familiar biblical figures and events, making The Last Temptation of Christ an extremely uncanny valley experience.

Scorsese roughly pulls the rug out from under the audience’s feet as he depicts the holy women of the Gospel as willfully trying to seduce Jesus. We are left feeling confused and almost uncomfortable with the depiction of foolish and ineffectual disciples presented before us, particularly Peter; whilst Judas Iscariot (who is vilified as a traitor in all the canonical Gospels) shines as Jesus’ confidante and even acts as his voice of reason and moral compass.

These are, however, mere little dizzying features within a hotbed of controversy: what floored and incensed audiences was Jesus himself.

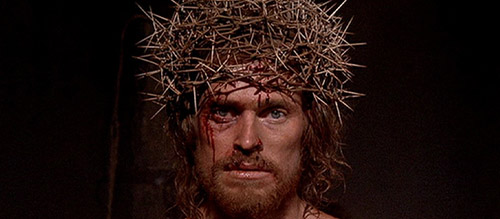

In the most original portrayal of Christ committed to the silver screen, Scorsese immediately upends all expectations showing us a man who knows he is loved by God and is trying to earn his hate instead – a goal he tries to achieve by making crosses for the Roman Occupiers to execute condemned Jews. Willem Dafoe, in the role of Jesus, plays a man who knows he is specially chosen by God, but for what he doesn’t really know: the entire film tracks his journey of enlightenment which he only fully realises in quite literally the final 30 seconds of the movie.

In the 2 hour and 44 minute run-time we witness the chaotic and painful reality of human existence through Christ. He is confused and agonised by God’s calling and initially reacts by ignoring and trying to drown it out. When he begins to finally submit to the calling, it is with timorous effort as he is plagued with self-loathing, convinced he is unworthy of God’s plan. Even once he begins preaching, he wildly alternates between absolute confidence and crippling doubt – the most memorable parables of The Gospels are butchered by a bumbling delivery to then be roughly overturned by terrifying acclamations.

The constant change is driven by a torturous slow reveal of God’s plan; previous self-assuredness whilst transforming water into wine quickly disappears to be replaced by cold dread as Jesus battles with the realisation of his full power and raises Lazarus from the dead. For many, these very human and natural inconsistencies are simply too much to bear to see in the image of Christ. At the very least, for the most open-minded viewer, it is very unusual to see such a vulnerable Christ; one who reacts viscerally to fear as well as emotional and physical pain.

The sight of a physically weak and needy Christ who desperately clutches at the robes of his friends so as to be supported, and who regularly seeks reassurance and comfort when frightened, is quite simply stunning.

The mystery of Jesus Christ’s physical existence was his experience of temptation (a piece of irrefutable Biblical canon) whilst still being without sin. In The Last Temptation of Christ, Jesus believes himself to be a sinner: but according to Sam “Burgundy” Scott in The Scorsese Experience: The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese allegedly states “He’s made to feel like he’s sinning – but he’s not sinning. He’s just human.”

Despite these directorial reassurances, there are scenes and images that contradict these claims in the most unsettling manner.

Even though he never lays a finger of her, there is definitely something uneasy about the image of Christ sitting in a prostitute’s residence amongst her (Mary Magdalene’s) eager patrons for an entire day.

Now, any enthusiastic Christian preacher will tell you with great vigour that Christ did indeed sit and eat with the sinner and whore, but I doubt none would claim that he would voyeuristically watch a working woman ply her trade throughout the day.

Whether it’s a sin or not, I don’t know, but I know it does feel much worse when you then realise that Jesus and Mary Magdalene have had a romantic history. Shuddering.

However, this is a mere herald to the coming travesty at the film’s peak. Like the Gospels, Jesus is betrayed, arrested and is condemned to death by Pontius Pilate. At the height of His Passion, whilst nailed to the cross, he is enveloped by sudden silence and is approached by an “angel” – she brings the message that God has decided that Jesus has suffered enough and that he does not need to die. She pulls the nails from his hands and feet, and kisses the wounds as Jesus accepts the proffered escape route.

Words cannot do justice to the horror of the audacious upturning of the central mystery of the Christian faith as Christ abandons his sacrifice – in one fell swoop Christianity is rendered obsolete; meaningless.

And for what does Jesus abandon his mission to redeem mankind for?

In short, a life of bodily pleasures.

He marries Mary Magdalene and even has a polyamorous sexual relationship with Mary and Martha (the sisters of Lazarus). With Christ being for millions of people the physical embodiment of self-sacrifice for the sake of humankind and for the salvation of our own souls, it truly stings to see him take the easy way out through a life of physical indulgence.

Critics’ anger and disgust comes from an even deeper and more basic root still – in The Last Temptation of Christ: An Essay in Film Criticism and Faith, the issue is articulated clearly and simply with: “I was just blown away by the wrongness of the very picture of Jesus kissing a woman.” (Note the irony that there is no anger caused by Jesus’ full on the mouth kiss with Judas.)

Kazantzakis’ intention for Jesus’ “Last Temptation” was that, although it covered years of Jesus’ alternative life, it actually run its entire course within the utterance of “Father, why have you forsaken me?”

It could be argued that as the final temptation sequence was merely an illusion, audiences could suspend their disbelief and just roll with the narrative of the “what if” scenario – but for those outraged masses, these heretical images, which bastardise The Gospels, have been committed to the screen and physically exist. Just like works such as “Piss Christ” by Andres Serrano, the provocative scenes from The Last Temptation of Christ will always elicit a fury that cannot be reasoned with, despite the artistic intentions.

With new lows achieved, such as depicting the Devil mocking closely held Christian traditions such as Veneration of the Cross, surely nothing of artistic or spiritual value can be found in The Last Temptation of Christ.

Evident in my writing thus far, I do empathise with the offended religious, but in reality I completely disagree with their outrage.

I am firmly in the Sam “Burgundy” Scott (of The Soloute) camp, who concludes in his essay that “The Last Temptation of Christ is a work of heresy make no mistake. It also one of the most Christian things ever put to film.”

Through my own Catholic viewpoint, I recognise that Scorsese has indeed earned a thump from Father Christmas himself, but the depiction of Christ he has to offer gives us the most realistic representation of the human struggle towards goodness that can actually relate to a modern audience.

My first reason for defending The Last Temptation of Christ is that both the book and the film are not mere crude, mean-spirited attacks on Jesus Christ or The Church.

Both Kazantzakis and Scorsese come from rich religious backgrounds and it is clear that the subject matter of Christ’s humanity is taken deadly serious by both men.

For Scorsese, who had wanted to make a film about Jesus’ life since he was a child, Last Temptation was an honest exploration of God, even going so far as to be quoted by ABC TV’s ‘Nightline’ that he was “disturbed” by the Catholic Church rating his film as “morally offensive”.

With childhoods dominated by Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox upbringing, Kazantzakis and Scorsese produce works which boast both a high philosophical and spiritual intelligence, so contrary to critics’ claims, the film’s most inflammatory and controversial scenes are not for mere titillation or sensationalism, but are part of a rich tapestry of a brave and genuine attempt at understanding one of history’s most influential and unusual figures. In The Last Temptation Reconsidered, Carol Lannone sets apart Kazantzakis’ “The Last Temptation of Christ” from other woks that desecrate the image of Jesus such as “King Jesus” (1946), as she sees it as “the effort of an ordinary man to understand Christ’s sacrifice from the inside out” and recognises that if a depiction of Jesus is “to speak to a modern man, he must be made to bear the infirmities of our age: doubt, angst, fear and trembling, existential dread and even the sexual obsessiveness.”

Scorsese succeeds in weaving these plights of modern man into his version of Christ and, at the deepest personal level, I found it arresting.

I am not a model follower of Christ. I would very much define myself as a bad Catholic. But, made clear in my writing back-catalogue, I would like to think that I attempt to know God better.

Since my childhood and its kid-friendly depictions of Christ that I became fond of, this has been the first time either film or television have presented a whole new facet of Jesus’ being which has physically deepened my understanding and, dare I say it, love for him.

Despite the ever-present pressure of modern society to shake off any embarrassing Christianity that is inflicted upon one’s self as a child, I never really joined the trend.

The main reason for this is that I find the person of Jesus Christ to be irresistibly attractive.

What I gravitated towards the most was the fact that despite his supernatural characteristics he was human – a being that could control the unfathomable forces of nature and bring the dead back to life, but one that would also pick his nose, would have to lean on a friend’s shoulder because they just twisted their ankle and who would also cry over the death of a close friend. I have the power to relate to the creator of the universe through my own ordinariness.

Through The Last Temptation of Christ, I witnessed how far this shared humanity truly went.

Willem Dafoe’s performance of Jesus made my heart physically ache as he experienced my very own struggles with faith. The hatred and disgust at my own shortcomings; frustration at the lack of sense in God’s work in the world, and the suffocating fear of the sacrifices that have to be made in order to submit to Fate.

Furthermore, I had never before contemplated the pain that could be caused by Jesus’ divinity onto his own humanity. Sam “Burgundy” Scott points out in his essay that “Scorsese seems to define humanity as Separation from God, all the more painful when He (Jesus) is God at the same time as He is His tormented mortal instrument.”

From a young age I have been told Christ died for my sins, and The Last Temptation of Christ had finally given me the bill: see a man terrified by his own miraculous powers, have his heart broken by asking his closest friend to betray him, and be dragged to a fateful death that every fibre of his mortal being struggles to reject.

I now realise why I’m supposed to tell God that I’m sorry.

My final argument is The Last Temptation of Christ validates the message of The Gospels more than any other timid non-offensive adaption, as it shows that even God recognises that the world’s salvation lies inescapably with The Cross.

Despite the undeniable peace and beauty of the ordinary life most people aspire to, Jesus rejects it with cries of “make me a feast!… I want to be crucified!”

Never have Jesus’ final words of his mortal existence – “It is accomplished!” – been so triumphantly proclaimed as he willingly submits to his Father’s will; redeeming mankind through his death (and eventual resurrection).

Ultimately, I’ve surrendered to to Decent Films’ damning conclusion:

“Only artists so steeped from childhood in the rich profundity of Christian Tradition could possibly create something so profoundly antithetical so that tradition, so deeply heretical and blasphemous.”

In the words of St Thomas Aquinas… “We ought to die excommunicated rather than violate our conscience.”