A Retrospective Look At ‘School of Rock’

The School of Rock was released in 2003, and if that doesn’t leave you questioning the space-time continuum and the entirety of your own existence then I don’t know what will. Can you believe it’s been nearly 13 years?

Richard Linklater’s Jack Black starring ode to Rock ‘n’ Roll was Paramount’s low budget comedy risk that truly paid off. Produced for only $31million, a relative drop in the ocean when compared to similar star vehicles of the time (Terminator 3 – $167million) and its immediate competition (The Rundown/Welcome to the Jungle – $85million), and Written by Mike White – the movie’s real Ned Schneebly – a screenwriter whose history of strange stoner comedies was perfect B Movie or straight-to-video material but rarely presumed to be anything more significant, School of Rock’s intricacies and impassioned collaboration in all aspects of its production became a critical success that pushed it to the top of the Box Office charts by its third week and pushed the movie to a $50million box office profit. What’s more is that it became nothing less than a cultural phenomenon that impacted the lives of many of the millennial generation and even defined the lives of a few others. Remember: “you’re not hardcore unless you live hardcore”.

At the heart of the movie is its music which was crafted with such an obvious passion by Craig Wedren, a composer whose life at the front of ‘post-hardcore’ band Shudder to Think (1986-1998) surely stood him in good stead for this movie’s symphony of rock and metal tributes. It’s like he was born for the role, as was the movie’s star Jack Black whose work perfectly complimented that of Wedren courtesy of a series of wonderfully worked improvised moments and a singing voice reminiscent of the glam-rock and metal bands left behind by the 90s’ rock music transition into Grunge and Nu-Metal. The passion of both artists is evidenced by their sensational collaboration that defined The School of Rock as one of the best music-based movies of this century and left at least one of its original songs on the MP3 players of most who came to adore it. Somehow, even while being set in a private school in the heart of white America, The School of Rock managed to pay an excellent tribute to the music and artists it had aimed to pay homage to while remaining accessible to newbies, entertaining to youngsters, and most importantly an admirable representation of one of music’s largest counter-cultures.

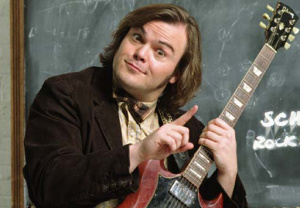

At the heart of the film is the performance of its lead star, Jack Black, for whom critical acclaim was becoming ever more synonymous with. Enjoying an extremely successful spell with his band Tenacious D in the early 2000s courtesy of rock hits such as ‘Tribute’, the two-piece’s front-man was becoming an increasingly wanted name in Hollywood, claiming a lead role opposite Gwyneth Paltrow in Shallow Hal (2002) and being one of the standout performers of a similarly music-enthused piece: High Fidelity (2000). The School of Rock marked the height of his film career, notching him a ‘Best Actor in a Comedy/Musical’ nomination at the following year’s Golden Globes and propelling him into the spotlight for many a leading role in the years to come. In the movie, he was nothing less than a tour-de-force; taking average or good scenes and transforming them into great or even iconic scenes that the director Richard Linklater let play out in long take after long take of pure musical passion from an actor who was clearly as in love with the source material as anyone else.

Richard Linklater’s position in the directorial chair is certainly one that cannot remain as underappreciated as it so surely is. The director, whose work on the Before Trilogy was mesmerising and whose work on Boyhood brought him oh-so-close to an elusive Oscar, has had a mixed bag of a career which has included a handful of classics and a handful of typical studio movies. School of Rock isn’t the sort of movie you’d associate with the director in either case, but his dramatic background and dedication to telling relatable character stories were qualities that the movie clearly benefited from, not just because of his motivation to leave the camera rolling each time Black went off-script. The director, along with cinematographer Rogier Stoffers, filled the movie with slow zooms or tracks that accompanied its long takes, requiring audiences to subconsciously recognise the journey the movie was going on and, arguably more importantly, pay full attention to the music that was being showcased. Think of Jack Black’s ‘the legend of the rent’ song from his opening day at the school… would it have been better suited to cut after cut of the childrens’ reactions? Of course not! It does not matter what their reactions are because we know what their reactions are, as we’re reacting in the same way. The camera was placed on their side of the class room, and the slow track out from Black performing the music not only helped us to recognise his vision but also slowly pay attention to different aspects of his performance and the absurdity of the situation in which his character was performing it in. A similarly as important achievement for the director was his work with the child actors, most of whom seemed comfortable in their roles throughout the movie, an element of the filmmaking process that requires a special gift and degree of focus from the director himself, as well as huge amount of patience. Each of the largely inexperienced cast was convincing enough to support Black’s superb performance, with their musical skills being celebrated by the filmmaker with every musical sequence; a sure sign of respect for his young collaborators that included children from a whole range of backgrounds and seemed to focus on each of them as individuals as opposed to stereotypes, bringing the music into focus and requiring the viewer to embrace rock and roll’s message of ‘it doesn’t matter who you are and where you come from, so long as you can play’.

Importantly, The School of Rock was released at the right time. The charts were filled with ‘pop rock’ groups like Blink 182, Sum41 and Black’s own Tenacious D, and school kids everywhere were embracing skate culture – Tony Hawks Pro Skater was one of the biggest selling video games for years in a row and baggy pants were all the rage. If you were a kid or a teenager in the early 2000s, you were bound to be involved in The School of Rock’s message in one way or another and that’s what made it so damned identifiable and so damned cool. For the less musically ‘cool’ kids in school corridors, School of Rock was a gift of musical credibility as well as a route into the enigmatic world of rock and roll that may not have otherwise existed in homes that did not often play songs of that type, whereas those already associating themselves with the happening music of the time could use School of Rock as reinforcement to their already existing thoughts of cool and rebellion, even if the latter was on an intrinsic or local scale as is the case with the characters in the story.

And that’s the key; isn’t it? The School of Rock was identifiable. Whether you were a school kid or an adult, a fan of the music or not, you could identify with its message, use it for credibility from your peers, or even let the rebellious side of yourself fantasise for 90 minutes or so. With a passion so contagious it was almost magical, The School of Rock left an indelible mark on the millennial generation through a production that transcended it’s children’s movie routes and became a cult phenomenon. The value of School of Rock goes way beyond its $50million profit as this Jack Black starring, Linklater directed, movie was has “touched these children” that have since grown to become adults and has cemented itself as one of the most unlikely of pop culture reference points of this century. Like it or not, The School of Rock is now etched into your psyche, and shall rightfully take its place alongside the likes of Juno and Napoleon Dynamite on the very short list of must-watch low-budget films of this generation.

I hated the film. No, I was not teacher’s pet, or remotely conservative. Yes, I love music. From The Clash, to Dylan, to Brubeck, Mozart and Bach via Creedence… and Herbie Mann; I love it. Black loves music as rebellion, which is fine – but just rebelling is pointless. What do we want? Something else, equally meritocratic, sexist and demeaning. When do we want it? Oh tomorrow or the day after – we’re hungover today. Why is the girlfriend wanting the Black character tomake a contribution “nagging”? Why is the effeminate gay boy a figure of ridicule? Why was this awful film ever made, and most importantly, what am I missing?