1917 Is Not Nationalistic

After three Golden Globes wins, a massive opening weekend at the box office, and ten Oscar nominations, 1917 appeared to be on top of the world. It wasn’t without its critics, though – even people who liked the film had their disagreements with its contents. In an article from Salon titled “1917 has one major flaw – it’s irresponsibly nationalistic”, the author explains the roots of the First World War, and asserts that any war film that fails to examine the causes is either a useful idiot for nationalism, or is itself nationalistic. This take misses a lot of the larger concepts within the film, and I will use textual evidence to show its values transcend the setting.

I want to begin this article by stating that I completely sympathize with the article’s perspective. We live in a time where a large segment of the global population feels anxious about the rise of populist politicians that exploit nationalism, “family values”, and religion to gain and abuse power. It’s also compounded by the appearance of collective apathy – it’s terrible how many (frankly, myself among them) are fine with sitting back and letting Robert Mueller or Nancy Pelosi do the work for them. I’m not a stranger to covering films that do promote and apologize for reprehensible or irresponsible ideas. 1917 is no such movie.

The Obligation of War Films

The article asserts that any war film is obligated to address the causes behind the conflict. “All of this needs to be said because a movie about World War I that completely ignores the ideology that begat that conflict is, at best, irresponsible and lazy. At worst it is implicitly nationalistic itself.”

If a film can be implicitly nationalistic, cannot it not be implicitly anti-nationalistic? Why is a film required to make background and subtext dialogue?

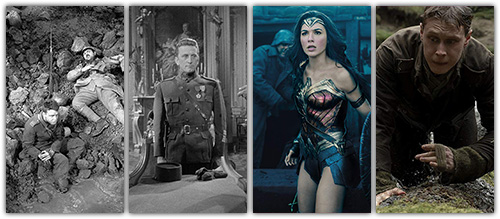

- All Quiet on the Western Front – “…openly denounced war and understood that its characters were pointlessly dying because powerful nationalist leaders had agendas that were indifferent to their fate.”

In 1917, Benedict Cumberbatch gives a similar speech about the pointlessness of the timing of the conflict, and bemoaned the leaders who, as the article clearly states, were nationalistic. If the general public is aware of that, as they are with the causes of the American Civil War and World War II, 1917’s obvious denunciations of war, death and nationalist leadership ought to be enough to satisfy the bar of the implicitly anti-nationalistic. If it’s not common knowledge (I wasn’t thinking about the causes of WWI during my showing, and as a “Hardcore History” listener I’m basically an expert), does it really matter all that much to the average viewer? Anecdotal, but not many detractors were ruminating on the various causes of WWI, they were mostly complaining about the editing, characters and/or story.

- Paths of Glory – “…told the story of French soldiers who were executed for cowardice when they were unable to perform an impossible task assigned by military leaders, men who used ostensible patriotism as an excuse for depraved self-interest.”

For those who are ruminating on the causes of World War I, it’s obvious. The film is not required to take time out of its script to say, “Oi mate, sure sucks our leaders are a bit into the ‘ole Patriotism, innit?”

The film’s display of the consequences of nationalism are the rivers and pits filled with dead men not unlike our protagonists. Not every film needs to reuse the same symbolism, or use military leaders as a vessel for politicians or political ideals.

- Wonder Woman – “…implicitly acknowledged the absurdity of that conflict when the protagonist confronted the Greek god of war Ares.”

David Thewlis and his hilarious mustache in cosplay is a reasonable implication for the evils of nationalism, yet none of the symbols in 1917 can stand in opposition so much as to even prevent this take?

This is the result of a severe aversion to treating this film as anything but what it is on its face, and looking at it through the lens of films that came before. The best films are able to send messages that transcend their material without battering you in the face – 1917 isn’t simply going to win Oscars for what it is as a technical marvel, but also for what that technical achievement did to enhance the material at the core of the film.

“…it is immoral to tell a story about a war without analyzing the reasons behind that war.”

This quote is a bit strong, and implies that there can’t be morals to a film if it doesn’t spend time preaching about one aspect of the cause. Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line is one of the best war films ever made, and it doesn’t spend time discussing fascism or imperialism. His film is the furthest thing from immoral, and exemplifies the idea that a war film can be about more than the literal conflict at hand.

“War is Hell” is Condemnation

The article mentions the evils of fascism and slavery for WWII and the American Civil War. I think we can all agree that the Holocaust and American slavery were a greater evil than the wars themselves – in fact, the article makes that distinction: “The Civil War and World War II were hell, but both needed to be fought in the name of a greater good. World War I was hell and was fought purely for the sake of the imperialist European powers and their various geopolitical and financial agendas. That is a critical difference.”

By showing the needless consequences of war, the film is showing the evils of nationalism and imperialism. Every dead or wounded soldier who had a family back home they would never see, all for something they really care nothing about; the abandoned baby thrust upon a neighbor who can’t even identify the mother – these are condemnations of the war and, therefore, nationalism. We can see the pointless tragedy for ourselves when people bleed out in front of an unflinching camera. This is all a part of the great evil of nationalism, unlike other conflicts that have higher values that necessitated the hell.

Introspection in 1917

“The military leaders on the British side are depicted as empathetic and wise; they are serious and blunt, to be sure, but only because circumstances demand that of them. When they make mistakes, it is because of faulty information, not because the system in which they are participating is itself fatally flawed.”

How should they have acted? Do we need to see them all embody the evil and absurdity of nationalism? Should they have been cartoon characters like in Wonder Woman to really get the message across? Should they be cruel, harsh or cold? Characters aren’t just hollow vessels that spout ideology, they’re also people. This war has been raging for three years, they’ve lost countless numbers of comrades – it isn’t crazy to believe that they have figured out how to effectively communicate and deal with those in their command. It’s naive to reduce these characters to models of militaristic stoicism. I believe they’re representations for how leaders ought to act towards people. They should be direct, empathetic, serious, and willing to admit mistakes, right? Isn’t that the opposite of someone like Trump?

“The closest thing to an exception is Colonel Mackenzie (Benedict Cumberbatch), who is depicted as so desperate to fight that he was willing to disregard direct orders and send his men into battle despite certain doom. Yet his actions are viewed as the flaws of an individual, not a system…”

Mackenzie’s decision is the definition of “making decisions based on faulty information”. He was sending his men into a trap because he believed he had the Germans on the run. His impatience and reputation for bloodthirst adds exactly the type of nuance previously implied to not be present. When we meet him, he discusses the futility of bothering with the incompetent higher-ups that don’t really care about the lives of the men.

And why should his faults be the faults of a system? Does this mean that the film should have implied British war strategy was to send 1600 men off to their death to represent the war in a microcosm? Should it have been said that the British weren’t careful in their decisions to send men off to their death? That’s exactly what the film presents. I’m not sure what it means to say “this is only the problem of the individual” in a context that we already agree was caused by nationalism – it doesn’t need to be explicitly stated to be clear.

“Meanwhile this modicum of complexity is completely missing from the opposing Germans. They are depicted as unilaterally evil: Sneaky, murderously attacking our heroes even when they show them compassion or rigging sadistic traps that horrify the protagonists and catch them off guard.”

I guess they could have inserted a scene where a German is helpful, but there are moments of humanity shown. When the German pilot’s plane crashes, Will and Tom save him because it’s the right thing to do. There’s a shot of one throwing up, clearly having some drinks with his pal. As Will chokes one out, they’re visually indistinguishable in the blackness, which I’d argue is a visual condemnation of the act and a statement about the similarities in servicemen on both sides of the conflict. Having a German soldier in a different light is certainly not a bad idea, but the moments where they are literally shown in a different light (the drunks and pilot lit by fire) that goal is accomplished in a visually poetic moment.

1917 Isn’t Just About World War I

Art isn’t just about one or two things, and isn’t only what it appears to be at face value (that would make Ares even sillier. Imagine if someone wrote that Wonder Woman excused the evils of nationalism by blaming it on the Greek pantheon). It has larger messages about conducting oneself in a conflict, perhaps one similar to the ideological rift that appears to exist in our modern culture.

The protagonists, Tom and Will, are two young men off fighting a war in another land that they clearly have no stake in. They aren’t concerned with the concepts behind the war, much like the typical person isn’t thinking beyond their own self-interest. Yet, they’re compassionate towards the enemy, they’re concerned about their families, and they tell fun stories to lighten their spirits in this dark time they inhabit. Put aside the facade of two British soldiers and see a grandfather who was forced into service. A lot of us in America have them too. There’s something we can relate to by seeing the hell they endured in a society that wasn’t prepared to deal with their affected mental state. This movie strips away romanticization of conflict to show pragmatic humanism.

Symbolism and Cinematography in 1917

The cinematography isn’t great because of its single take, which is certainly an impressive illusion for something of this scale, but also because of how well it conveys the themes visually. The orange throughout the film represents humanity. We see it in Tom and Will’s uniforms, the sandbags piled around them, the dirt as they cross in No Man’s Land, the fire in Écoust, and the plane. The dirt, trenches and church fire show the darker side of humanity – the absolute wasteland we created with weapons is a stark contrast with fields shown at other times – while the fire in the French woman’s home shows a brighter side of self-sacrifice and care. In the briefing scene it illuminates the conflict of the film while also portraying the struggle between man and it’s greatest enemy: an encroaching end.

Orange is in concert with its analogous color, green, showing man’s codependent relationship with nature. The rolling hills of the French countryside illustrate that there is still good in the world, and not all has been tainted by those who seek to fight and destroy. The soldiers may scoff that this is what they spent three years defending, but Will and Tom, as we see in the opening shot and closing shots, are in tune with that goodness. There’s plenty to love and defend when it comes to our world, and we shouldn’t give up our fight for that. 1917 litters the film with the symbols of hope; the cherry blossoms being the most prominent, but there’s also the milk, the trenches upon reaching his destination, and even the bunker rubble, each showing a positive emerging from a negative. There’s an optimism for the future, that we can achieve what we hope to achieve in the world, thereby saving lives.

World War I was supposed to be the war to end all wars, but it wasn’t. There was World War II, the Cold War with its mess of ideological conflicts, and the American invasions all over the Near East. There’s always hope we can solve the conflict, and not to go all hippy-dippy, but that does start with compassion. It starts with how we engage with those who are sneaky or sadistic, and there’s no point where the characters treat the “other side” as an absolute other.

Conclusion

The idea that 1917 is implicitly nationalistic is dissonant with an examination of the film’s visual text. This is the pinnacle of plot-driven storytelling because of its ability to express themes and ideas without bashing the viewer over the head with preachy scenes of dialogue. Continued engagement with such a notion when there’s clearly no bad will from the filmmakers does an absolute disservice to them and the films that actually contain sinister messages.