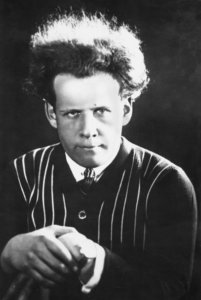

An Artist’s Contributions: Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein

This short feature is intended to be an introduction to Soviet Montage and Eisenstein as part of the Soviet School. Given the complexity of the topic, it is not to be considered an exhaustive piece on the subject.

While avant-garde movements were spreading all over Europe, Russia was no different. The most prolific period for Russian avant-garde artists dates back from before the first World War; it overlaps with the Russian Civil war (1917-1922) and after that, with the Soviet regime. The Russian avant-garde movement brought about new theories and is accredited as being a force for social changes that were also introduced in contemporary Russian society with Formalism in literature, Constructivism in the arts, and with Mejerchol’d’s (translated to Meyerhold in English) Biomechanics theory regarding theatre acting. Eisenstein and many other important soviet directors were trained in Mejerchol’d’s theatre in Moscow and they drew inspiration from these experiences to create their own style of film. In cinema, Lev Kulesov is considered a pioneer and one of the most prominent members of the Moscow Film School, which was the world’s first film school. He was famous for the Kulesov effect and his new theories regarding the Soviet Montage, that was later developed by fellow MSS attendees Eisenstein and Pudovkin.

Eisenstein’s first feature length film was ‘Strike’ (1924), in which he used the so-called “Montage of Attractions”. This technique consists of associating images or frames that were in contrast with each other in order to convey a symbolic message. An example of his work where this technique was most evident was in the alternating footage of the slaughter of a cow and the rioting of factory workers, many of whom are killed by the soldiers sent to quell the riot. By associating these two very different moments so closely in the same scene, Eisenstein perfectly conveyed the ideas of the Revolution and the suffering of the people brought about by social injustice and hunger.

In his later works, this kind of montage kept developing into something even more complex, leading to ‘Battleship Potemkin’ (1925) and ‘October’ (1927), in which Eisenstein developed the intellectual montage. This consisted not only in a contrast between the frames but also of elements within each frame, thus creating complex meaning that the audience had to grasp by association.

An example of this can be seen in sequence showing a sailor wearing a striped T-shirt while violently smashing a plate — the stripes on his shirt are to create a contrast with the vertical stripes of the wall that can be seen in the background.

Eisenstein was also notable for his decisions to often overlap time in order to show an event from different points of view; a technique that was popular in the silent era yet seemingly used with deeper meaning in scenes such as the one outlined above, where the sailor reads the inscription on the plate he is washing – which translates to : “Give us this day our daily bread” – then becomes angered, smashing the plate as he thinks about the conditions in which those like himself are forced to live. Eisenstein shows us this action through a succession of short shots: first, we see a little distant shot of the sailor caught in the action of smashing the plate; right after this, we see a close-up of him performing exactly the same action as if time had stopped and the action lasts longer than it would do in reality – it is in fact just showed from different angles while frames flash on the screen. This use of time was of course not realistic, but it conveyed the revolutionary message that the soviet cinema was interested in pursuing. Eisenstein wanted to achieve a conceptual meaning through the use of restless cutting. It was simply revolutionary at the time.

Another example of overlapping time and short cuts is in a scene in which sailors throw a doctor overboard – when you watch this scene it is obvious that the action is repeated from different points of view.

In these two sequences both the overlapping of time and the related use of snappy cuts have a symbolic meaning that is demanded to be understood by the audience – Einsenstein’s aim was to stir up the emotions of the viewer and convey a social message.

In another of his masterpieces, ‘October’ (1927), Eisenstein used the technique again, this time when presenting Kerenjkij opening the door to the Tsar’s throne room, repeating the action twice without continuity.

In this picture, the famed director also uses the intellectual montage to associate Kerenskij with a peacock, a flaunting animal which comes to represent the character’s vanity. He presents two frames of Kerenskij’s boots and finally another one of the Romanovs’ coat of arms, thus symbolising his continuity with the Tsar’s empire and his egocentrism, both of which were in contrast with the beliefs of the Revolution. Everything Kerenskij does is not as the on-screen captions tell us – these are supposed to be the actions of a true democrat – but are instead another form of oppression. In this way, Kerenskij betrays the true spirit of the revolution. Eisenstein decides to use the intellectual montage and a rapidly paced form of cross cutting without continuity; elements which, when considered singularly, would not have any meaning, but are brought to life when forged together in association with the written narrative through such a technique.

Although these techniques are the most important of Eisenstein’s style, he also believed that his montage theory should be extended to every expect of filmmaking, including colours and light. In terms of his own work, the two main examples of him putting this theory into action exist in ‘Alexander Nevsky’ (1938) and ‘Ivan the Terrible’ Part One (1944) and Part Two (1958). In ‘Alexander Nevsky’, he dressed the knights in white to express oppression and cruelty, whilst he associated black with patriotism and heroism which belonged to the Russian militia. By doing this, Eisenstein wanted to prove that colours don’t have a specific meaning of their own and if they are taken out of a given context and put into a new one, they will take on a different meaning; a circle that shall never end.

Moreover, Eisenstein famously used colour in ‘Ivan The Terrible’ in a long sequence that led to the death of the on-screen character of Vladimir Andreevic, while the rest of the film was presented in black and white. This choice is of course aesthetic, since it gives much more pathos and drama to the episode, but it remains an important example of the filmmaker’s thinking; thinking that would prove to be ‘too complicated for the general public’ through the decline of his popularity.

Conclusively, Eisenstein’s work was so heavily associated with the Soviet State of Russia that it therefore went underappreciated in Western culture for much of his prominence, with his theories having to wait to find the credit they deserve as regards analysis and tribute, much of which has been applied in films from almost every decade since – it’s tough to think of a film such as Steven Spielberg’s ‘Schindler’s List’ without such a colour technique as the one used in ‘Ivan the Terrible’, for example, or the stairs scene in Brian De Palma’s ‘The Untouchables’ without the montage theory applied in Eisenstein’s ‘Battleship Potempkin’. Eisenstein’s great impact on Soviet cinema is perhaps untouchable and his lasting impact on mainstream American cinema is as strong as the impact of any foreign filmmaker. He is a filmmaker who now holds a legacy beyond that of his diminished popularity towards the latter stages of his career and is rightfully celebrated for his contributions.

Recommended for you: Our “Where to Start with” Series

Bibliography and further reading

Ejzenštejn, Sergej. Il montaggio. Marsilio, 1986.

Ejzenštejn, Sergej. La regia. Marsilio, 1989.

Somaini, Antonio. Ejzenštejn. Einaudi, 2011.