Where to Start with Jim Jarmusch

When it comes to American independent cinema, few filmmakers embody its true essence as much as Jim Jarmusch; he is an artist who has never been tempted by the mainstream. Despite dabbling in subject matter such as vampires, samurai and zombies, the films of his that represent these feel more like the antithesis of the genre they’re serving in. In that sense he is uncompromising – the type of filmmaker so many aspire to be yet so few are able to match.

Jim Jarmusch began his filmmaking career with Permanent Vacation, his final year university project released in 1980. His second film, Stranger Than Paradise, was one of the more prominent films in the 1980s independent scene, being a major part of the No Wave movement. No Wave cinema was a period of underground filmmaking from 1976-1985, and its films were categorised by their stripped down and guerrilla filmmaking techniques, with stories that featured darker moods than standard Hollywood pictures. As a leading figure of this movement, Jarmusch soon captivated a cult-like audience of outcasts and rebels. These early works would solidify his role in cinema as the cool auteur, and his later career would only cement that legacy as he attracted a consistent pool of talent, such as Tilda Swinton, Bill Murray and Steve Buscemi, all popular actors within film fan circles.

Despite often being associated with a particular style, Jim Jarmusch’s filmography is surprisingly varied. His career can be split up into three distinct eras…

The first is this aforementioned No Wave period, in which Jarmusch develops his skills as a filmmaker and his signature style becomes apparent. From Permanent Vacation (1980) to Down by Law (1986), these films are gritty and relentlessly down to earth – even the lens itself feels dirty.

The middle period is marked from Mystery Train (1989) until Coffee and Cigarettes (2003). Here, Jarmusch evolves his style and applies it to new scenarios. He experiments with form and dabbles in new genres such as the revisionist western and martial arts. The results are hugely successful and this is arguably his most creative period as a filmmaker.

The final and current period is a combination of the previous two. Here, he seems to focus on slower and more thoughtful pieces whilst still utilising his signature playfulness of form, reflected both in genre and structure. This is Jarmusch at his most refined. The old Jarmusch is still very much present, only he now has decades of experience.

The three films below have been chosen to best represent the three respective periods of Jarmusch’s illustrious career. The goal of this Where to Start with… guide is to give insight into these different parts of this great filmmaker’s forty-plus years in the industry and give you the opportunity to choose a path that best suits your interests. This is Where to Start with Jim Jarmusch.

1. Down by Law (1986)

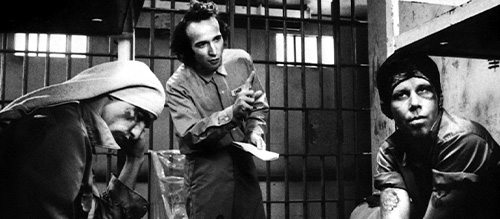

As the third feature of Jim Jarmusch’s directorial career, Down By Law takes all the qualities of the director’s early films and perfects them – the minimalist yet lived-in sets, the griminess of real life, and the microbudget that forces creativity. While his first two films can confidently be classed as No Wave, Down by Law feels like the culmination of these efforts due to a more ambitious story and many refined techniques.

Zack (Tom Waits) and Jack (John Lurie) become acquainted in prison after they are both wrongly accused of a crime. They share a cell with Bob (Roberto Benigni), an Italian tourist imprisoned for accidental manslaughter. Zack and Jack’s strong personalities cause them to clash, but when Bob strikes a plan to escape they form a mutual respect for each other – the trio’s relationship is at the forefront of the film as they go on the run. The film progresses into a road movie, giving small glimpses of a dishevelled America at that time. The found family aspect between the three leads is unexpectedly heartwarming amidst this bleak and dismal setting.

Down by Law is a testament to the type of dramatic tension that Jarmusch prioritises. The actual prison break is omitted from the film, as we only see the aftermath of the trio escaping. While such a strange choice would be frustrating in another filmmaker’s hands, with Jarmusch it makes complete sense. The temptation to centre the film around the escape would have undoubtedly been there, but Jarmusch rejects genre conventions to focus on something more important: character. The tension in Down by Law comes from the character’s relationships. As will become apparent with the other films mentioned in this guide, Jarmusch is a firm believer in character over plot.

It is a joy, then, to report that the characters here are played to perfection. Musician Tom Waits is disc jockey Zack, who is paired brilliantly against Jack, the charming pimp played by John Lurie. They each have rough exteriors, yet Jarmusch takes the time to develop them naturally so that we can see and appreciate their softer core. Roberto Benigni as Bob is the scene stealer, however – bringing a much needed levity that superbly contradicts the down-and-out attitude of the other two leads. Unlike them, he shows goodness on the outside, becoming the heart of the group. A scene in the prison where he gets his fellow inmates to chant: “I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream,” is nothing short of hilarious and cements him as one of the best characters across Jarmusch’s oeuvre.

Great performances, coupled with stellar black and white cinematography by frequent Jarmusch collaborator Robby Müller, make Down by Law the perfect entry point for someone wanting to scratch that 80s American independent cinema itch.

A film about losers that will likely be enjoyed most by losers due to the relatability of the three lead characters, Down by Law is a film that feels genuine and endearing.

2. Mystery Train (1989)

For his fourth feature, Jim Jarmusch abandoned his at-the-time trademark of shooting in black and white. Mystery Train acted as the introduction to a new trademark: the rockstar.

Throughout his career, the director has utilised many facets of rock music to inform his filmmaking choices. Sometimes this comes in the form of casting a rockstar, such as Iggy Pop in various roles, or sometimes it’s through his use of rock music in his film’s soundtracks, such as when Neil Young scored Dead Man. In Mystery Train, it’s the subject matter. At the film’s forefront is Elvis Presley, whom Jarmusch is a big fan of. A choice like this illustrates how Jarmusch’s personal touch is all over his projects; he makes films that appeal to his own interests, and they therefore feel more rewarding to watch, as if each film is teaching us more about him as an artist.

Mystery Train is also indicative of another stylistic choice that Jarmusch often makes: the anthology film. This is the first instance of Jarmusch experimenting with form. He has multiple anthology films, such as Night on Earth and Coffee and Cigarettes, but Mystery Train is the most satisfying due to its unifying themes being more apparent.

Mystery Train is split up into three stories, each taking place in Memphis, Tennessee. The first follows two teenagers from Yokohama on a pilgrimage to Memphis. They are huge Elvis fans, with their segment acting as a whistle stop tour of some of the city’s most famous landmarks, such as Sun Records. The second story follows a woman who is stranded in Memphis. She has unusual run-ins with the locals and is even visited by the ghost of Elvis. The final story showcases three of the residents of Memphis as they hide from the police after drunkenly shooting a liquor store clerk. The three stories are linked by the Arcade Hotel, where each character spends a night. The hotel is run by the comedic duo of the night clerk and bellboy, whose interactions with the guests are some of the film’s highlights.

Jarmusch treats Memphis with as much importance as he treats each character. Really, the city is the star of the film. Here, Memphis is a three-dimensional place, reflected in the varying ways it’s portrayed. The three stories each explore a new way to view the city.

In the first story, the characters have travelled there purposefully, and to them the city is heralded as a holy place. The second story is about someone who did not choose to be there, therefore we see a disdain for it. The final story follows three people who already live in Memphis. They’re familiar with the city, so to them it’s a playground – they act wild and get drunk, they walk into the hotel and get a room easily because they’re locals. Contrast this to the other characters: the first story’s couple don’t fully understand the desk clerk due to language barriers, and the woman in the second story must share with someone she doesn’t know. Jarmusch explores how the same city can have completely different effects on a person, giving us a full 360-degree view of this place. By the time the credits roll, we have become residents ourselves. In under 2 hours, Jarmusch has shown admiration, loathing and uneasiness for the same place in a way that is perhaps evocative of the complex relationship he has with his nation as a whole, the United States.

That’s not to say that the focus on location detracts from the characters at all. The opposite is true in fact. Since we are given such a broad scope of Memphis, there are a plethora of offbeat characters that make the film as fun and charming as it is. The night clerk, played by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, is a particular highlight, dominating every scene he is in due to his theatricality. Physically he stands out too, due to his bright red suit that captures his electric personality. Steve Buscemi gives an expectedly great turn as Charlie in the final segment, where he acts opposite musician Joe Strummer who plays Elvis lookalike Johnny. These interesting characters help flesh Memphis out even further, making it feel lived in. They have a timeless quality to them, as if living in their own plane of existence (much like the rest of the film, which feels ever so slightly out of time). It’s rockabilly in a contemporary setting – a celebration of the past in an unsure present.

3. Paterson (2016)

The most recent film on this list, and perhaps even the greatest, is 2016’s Paterson.

Paterson is a film that represents much of Jarmusch’s later filmmaking period which focuses on feelings rather than events. Also included in this era of Jarmusch’s work are The Limits of Control (2009) and Only Lovers Left Alive (2013). Interestingly, both films take a character archetype (assassins and vampires respectively) and explore it in a way that feels fresh. Instead of making that archetype his film’s defining characteristic, Jarmusch uses it as a springboard to develop meaningful characters worthy of investment. Paterson is a film about the everyman; that everyman being Paterson, who coincidentally lives in Paterson, New Jersey. The mundanity of a blue collar worker’s life is the focal point of the film as he finds happiness in art and the small details of his day to day. Captured with sincerity and nobility by Adam Driver, Paterson must be one of the most likable characters in all of cinema. Driver is a physically imposing guy, but Jarmusch doesn’t play into this – instead, his strength comes from kindness and a gentle sincerity that many people should strive to achieve.

Summing up the plot of Paterson can be quite difficult. This is not due to any intense complexities, but rather the opposite. Not much happens in the film, the narrative following the titular character’s life as a bus driver. From the amusement of overheard conversations to the awe of a chance encounter, everything that happens to Paterson feels so refreshingly regular – there isn’t even a build up to a climactic third act. The big events in the film, such as Paterson’s bus breaking down, are shrugged off as inconveniences. Once again Jarmusch resists the urge of other filmmakers; the idea of a monotonous life would typically be the foundations of a nightmare, but Jarmusch makes it seem joyous.

In his spare time, Paterson writes poetry. His poems are about small and personal things, from his wife Laura to a box of matches, yet this simplistic beauty enriches the world around him. Real-life poet Ron Padgett provides these for the film. Again, Jarmusch pulls from his own experiences as the two studied poetry at Columbia University. The results are beyond excellent; Padgett’s poems are the perfect paint for Jarmusch’s melancholic canvas.

Structurally, the film is as poetic as its subject matter. Each day is signified by a title card, clearly segmenting the film in a way that feels like stanzas of a poem. Rhymes are represented by repeated scenes such as Paterson waking up or going to the bar. The motif of twins and Laura’s obsession with patterns bleeds into the set design, suggesting the carefully constructed art of an author familiar with poetry. It’s this playfulness with form that reminds us that Jarmusch is still finding ways to be inventive as a director. This is never overbearing either – much like the film itself, Jarmusch’s techniques are understated. His filmmaking feels effortless despite being meticulous.

Paterson is a quiet and meditative piece. It is Jarmusch’s ode to the mundane. Despite its small scale, the film manages to be profoundly inspiring. Most people will feel overwhelmed by life, but Paterson is that reassuring hand on your shoulder, the voice that says “take it slow”. Jarmusch issues a passive call to action for everyone to stop and appreciate where we are. He directs a film that breathes freely and lives by its own rules. For a certain type of person, Paterson will be that rare perfect film.

In large part due to this filmmaker getting carte blanche since his debut, there are very few misfires in the Jim Jarmusch filmography. His films are controlled, and the clear authorship makes even his weakest feature a worthwhile viewing experience. He is a filmmaker who never sacrifices artistic merit for mass appeal, instead making intelligent and thought-provoking pieces while never falling into the trap of being pretentious because of his tight grip on what’s cool. If any of these films appeal to you, then please do explore this great American filmmaker’s work – with almost all of his films falling below the 2-hour mark, it won’t take long before you realise you have a new favourite director.