Where to Start with Akira Kurosawa

This article will be exploring some of the best works of iconic Japanese director Akira Kurosawa and is intended to be a starting point for those who are not familiar with the work of this hugely influential figure of East Asian cinema.

Akira Kurosawa, born in Tokyo in 1910, is regarded as one of the most influential directors of all time, not only for his skills as a screenwriter and director but also for the influence his movies have exerted over western cinema, most reputably on Star Wars. For all of the great filmmakers to descend from Japan, Kurosawa is noted as being perhaps the most influential as regards the spreading of Japanese culture, history and ideologies worldwide.

The three works outlined in this article are a recommended guide on how to approach Kurosawa’s ouevre for the first time. This list will not include Rashomon (1950), which is arguably his most notable work and was an influence on many other filmmakers due to its new narrative technique (known as the ‘Rashomon effect’), because it is a very complex film for many reasons beyond that of its directorial style, and therefore not the best place to start when attempting to become familiar with the director’s filmography.

The three films selected here are instead ones that accurately illustrate a continuity in terms of genre, setting and score across Kurosawa’s long and respected career. All three can be ascribed to the Jidaigeki genre, that is the Japanese term used to describe period films set in historical Japan, and each is a remarkable and hugely reputable release worthy of consumption for any fan of the cinematic art form.

1. Seven Samurai (1954)

The first film to consider, and perhaps the most well-known, is Seven Samurai.

Filmed in black and white, the story takes place in 16th century feudal Japan. A village of farmers are attacked by bandits and, as they fear the bandits will come back and steal their harvest, the farmers seek the help of a group of samurai they recruit on the streets.

The recruitment sequence in Seven Samurai is an example of the balance between comic and serious events Kurosawa manages to achieve in this film and throughout much of his career, showcasing his unique sensibilities alongside that of the proud spirit and valour of the samurai (a recurring feature of most Kurosawa works). Only a group of seven samurai, who are selected through a series of tests of their real worth, accept to help the farmers. The story centres first on the recruitment of the samurai, then mostly on the preparations for the looming attack, whilst frantic action sequences are limited to the very end.

Kurosawa’s excellent casting choices here include Toshiro Mifune as Kikuchiyo and Takashi Shimura as Kambei Shimada – both stars of the Japanese screen who act in many of Kurosawa’s films and have thus become popular internationally. Mifune’s charisma and acting skills made Kurosawa notice him when he gave him his first role in Drunken Angel (1948). Here Mifune proves to be a versatile actor, delivering both the most dramatic moments of Seven Samurai and providing comic relief. His performance is worth the price of admission alone.

Seven Samurai’s sequences showing the farmers and the samurai as they chase bandits are the most notable and impressive in terms of techniques used. Kurosawa often resorts to long takes and wipes in the edit, instead of cross cutting. He also prefers long (or medium wide) shots to close ups.

The moral message is delivered by the main characters: in feudal Japan class distinction cannot be overridden and living conditions for Japanese people are extremely brutal and precarious.

The score by Fumio Hayasaka is a successful blend of Japanese and western music – sequences featuring working farmers are set against the backdrop of traditional Japanese instruments and sound, while in battle scenes and dramatic moments the music changes to an epic tone that is more distinctively western.

This unique musical style and Kurosawa’s directing style are to be found, with a few variations, in the films that I am going to mention next, connoting his ever-recognisable impact on each of his works.

Recommended for you: Star Wars Live-Action Movies Ranked

2. Throne of Blood (1957)

The story of Throne of Blood is based on Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” and, as Seven Samurai was, is set in Medieval Japan. It is an adaptation freely inspired by the original play, as the setting and elements of the plot have been adapted to the Japanese society of the time (for example, an evil spirit stands in for the three witches in the play).

Although the film’s composer Masaru Satō incorporated elements of western music, the overall sound, tone and setting are more typically Japanese than in the Shakespearean play, thus helping to differentiate this pre-eminent Japanese story from other adaptations of “Macbeth”.

At the beginning of the film, a Japanese chant echoes in the fog. The same sequence is also repeated at the end, creating a ring composition where the fog functions as an omen – it appears either when some tragic event is about to happen, or before the evil spirit appears.

The local lord Tsuzuki is waiting on news from his loyal generals, Washizu and Miki, who are fighting against traitors. While coming back to the castle, the two lose their way in the thick forest that surrounds it, and they meet a spirit that predicts their future. Washizu will become the lord of the North castle whilst Miki will become the commander of the first fortress. The two men do not believe the spirit’s words, but when the first part of the prophecy becomes true, Washizu, instigated by his wife Asaji, decides to take action. This acts as the trigger point for the tragic events that follow.

Like in Seven Samurai, there are notable acting performances. Seven Samurai’s Mifune, in the role of Washizu, delivers an excellent performance throughout, but is most notable in a sequence of madness towards the end. Takashi Shimura, also cited in Seven Samurai, shines here as Lord Tsuzuki’s advisor Odakura Noriyasu.

Kurosawa uses similar techniques to the ones in Seven Samurai (long, medium wide and full shots) but also many deep focus shots. During dialogues between Washizu and his wife Asaji (Isuzu Yamada), Kurosawa opts for wide shots and different camera angles (mostly Dutch angles and low-angle shots). It is also important to note the use of drums that, like in Seven Samurai, announce a battle.

The moral message here is less hopeful than that in Seven Samurai: although those who sought power eventually perish, the film shows man’s changing and fragile nature when faced with moral dilemmas.

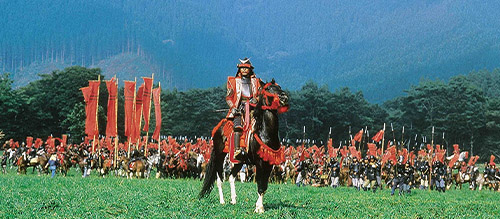

3. Ran (1985)

In contrast with the two films outlined above, Ran is the most pessimistic in terms of message and general tone, conveying a philosophical and mystical approach to life that doesn’t leave any room for optimism but makes men fall into complete despair without any hope for redemption.

Even the good-hearted and religious characters that are spokespeople for a Buddhist way of life do not have a chance to be saved in this egoistical world. In contrast with the director’s other entries in this piece, this film is in colour, the specifically traditional and focused aspects of the black and white pallet brought into a more typically glorious visual presentation that does not fail to disappoint.

The story is set in feudal Japan and it starts with a hunting sequence – featuring the main character Hidetori, played by the famous and talented Tatsuya Nakadai.

After the hunting sequence, the following sequences are filmed in static shots – full and long shots with no use of cross cutting (which again confirms Kurosawa’s preference for these techniques). The story — inspired by Shakespeare’s “King Lear” — is about Hidetori, the old chief of the Ichimonji clan, who wants to leave his power and property to his three sons: Taro, Jiro and Saburo. Jiro’s thirst for power will make him fight against his brothers, leading to tragic consequences.

What makes this film different from the previous two is not only its more pessimistic message and visual presentation, but also some choices in terms of sound and score.

The composer Toru Takemitsu uses sounds and noises from the natural world (for example the wind, the sound of a fire that burns Hidatori’s castle to the ground, birds singing). He also uses silence as a means of communication between the characters and as an auditory backdrop to the characters’ inner thoughts. In Ran, like in Throne of Blood, drums are ever-present, as they are associated with the approaching battle.

As in the previous films mentioned, the cast in Ran is excellent, especially Tatsuya Nakadai’s impressive performance as Hidetori. What perhaps strikes the viewer most about Ran is the seemingly less balanced succession between lack of action on screen and violent, brutal battle sequences (such as the attack of Hidatori’s castle and the battle between Jiro’s army and Saburo’s towards the end of the film). The battle scenes show man’s ruthless nature, as the camera focuses on the dead, thus emphasising the senseless slaughter.

Recommended for you: Akira Kurosawa, Toshiro Mifune: Cinema’s Greatest Collaborations

Finally, all three films share some continuity and differences that make them easily watchable one after the other. They share the epic atmosphere of feudal Japan, showing the interest Kurosawa had for this period of Japanese history. Most importantly, it is interesting to watch how he was able to recreate the atmosphere of that historical period on screen, with beautiful costumes, talented casts, capable and innovative composers, and of course his exceptional directing abilities and skills. For these reasons, there is simply no better place to start with arguably the greatest Japanese filmmaker of all time than with the three movies outlined in this piece; three films that showcase the style and genius of the ever-great Akira Kurosawa.