The Ring, The Grudge – Redefining Horror

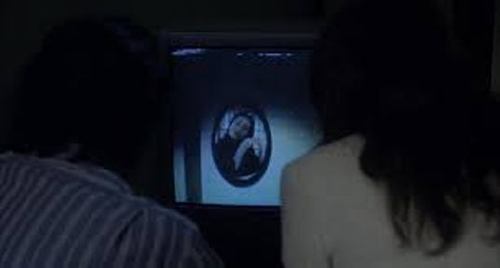

Ringu (The Ring)

Directed by Hideo Nakata (1998)

Ju-On: The Grudge (The Grudge)

Directed by Takashi Shimizu (2002)

Onryō (Japanese)

A vengeful spirit believed to be capable of causing harm in the world of the living, killing enemies, and even causing natural disasters to exact vengeance to redress the wrongs it received while alive.

Most people are familiar with Sam Raimi’s supernatural horror franchise The Grudge (2004-2009) and Gore Verbinski’s The Ring (2002), but not everyone is quite as familiar with their original Japanese counterparts, or aware that they are even remakes at all. In the 1990s and early 2000s it was Japan’s turn to be recognised as a serious contender on the horror cinema front and with many of their productions spawning big budget American remakes The Ring and The Grudge being perhaps two of the most famous.

There is something infinitely scary about Japanese horror cinema, something difficult to define, something that is hard to find in cinema from any other country or culture, something that just isn’t present in their western remakes, or indeed in any western horror films.

There are many ways of examining Japanese horror films, or indeed any cinematic output from Asia, there is looking at films in terms of their country of origin, as national cinema and as a way of expressing that country’s national identity, or in relation to public affairs within the country, whether for propaganda or critical purposes. There is the option to examine them in terms of western horror film academia, applying western film theories, for example Robin Wood’s “Basic Formula” for horror films in his essay The American Nightmare, or Barbara Creed’s theories surrounding the “Monstrous Feminine” in her book The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis.

The other popular theory used for examining and analysing Asian cinema is that of “Orientalism” a theory popularised by Edward Said in the 1970s, which claims that “The Orient” is basically a place of western invention. A strange and mysterious land existing to the east of Europe, it is romanticised by the west as a paradise land, filled with beautiful, exotic beings and new experiences as well as haunting and beautiful landscapes. “Orientalism” is a mass generalisation of thousands of cultures from the Caucasus region, through the Middle East and the Indian Subcontinent to the Far East and thus becomes very problematic in that it reduces the vastness of the Asian continent down to the idea of one single ‘culture’, universal throughout the entire continent.

However, this idea of “Orientalism” may explain why Japanese horror films such as Ringu and Ju-On provoke so much fear amongst a western audience, as well as offering an insight into what is missing from the western remakes.

These days the idea “Orientalism” promotes: that Asia is a paradise land, an escape from western capitalism and consumerism, is clearly seen in the “Gapper” market: backpacking India, Thailand, Nepal and Myanmar (Burma) to name a few in the hopes of “finding oneself” somewhere along the well worn “Hippy Trail”. Whilst many westerners have an idea of what to expect, and of the vast differences across this huge continent, there are still those who flock to Asia expecting a continent filled with hot, sunny beaches the same as those in Goa and Thailand, monuments like the Taj Mahal or Angkor Wat at every turn, healthy, organic food with no McDonalds in sight, beautiful available women (remember “Thai Brides”?) and simple locals who know nothing of the hassles of “modern life” and still collect their water from the well every morning. And all available on a very small budget.

Losing yourself in amongst all the beaches, temples, delicious food and beautiful people, at the cost of £5 a day? Sounds idyllic doesn’t it? And whilst this may represent a tiny portion of Asia, it does still completely ignore the vast majority of an entire continent. Enter Japanese horror, or J-Horror.

In this paradise land, who would be expecting vengeful spirits to haunt their former stomping grounds, hell bent on revenge, leaving a trail of death and destruction behind them? And when something horrific happens in a perfect setting it seems all the more tragic, despite the fact that both Ringu and Ju-On use the common J-Horror trope of the “Onryō”.

Onryō is a character found throughout Japanese stories and folklore dating back as far as the 8th Century, and is a vengeful spirit, usually one who died in the grip of powerful rage or extreme sorrow, looking to exact revenge for the wrongs suffered whilst they were alive. An Onryō is believed not only to have the power to harm or even kill their enemies but also cause natural disasters.

In comparison to western horror cinema, it seems that in Japanese horror films such as Ringu or Ju-On, there is no way of defeating the evil or monster of the story, instead the evil spirit just carries on killing. This idea of evil triumphing over good is one that goes against most traditional horror film story arcs in western horror cinema. The traditional horror story shows normality (usually the ideal family life) being threatened by the monstrous, who is always “other” in some way, be that as an actual monster or a human being considered different to normality in some way. Throughout the film the monstrous creature or character terrorises normal life in some way but it ultimately defeated by a character on the side of normality, be it the family, or an authority figure. It is the classic good guys vs bad guys where the good guys always win.

Even in western horror films when evil triumphs over good there is usually still some sort of ending to the story, some way in which the audience knows the story is over. Whereas neither Ringu nor Ju-On offer any sort of resolution or closure to their respective stories, their curses seem to pass endlessly on to anyone who happens upon the videotape in the case of Ringu or anyone who enters the house in Ju-On.

These examples of Japanese horror cinema rely mostly on the use of psychological horror, cleverly and carefully crafted stories with fairly minimal amounts of violence and gore, and no final resolution, no happy ending, or as happy an ending as you can get in a horror film. As well as showing that the mysterious paradise land western culture has created through “Orientalism” is in reality no safer, no simpler and no more ideal than western culture, it is simply different. There is no escape from horror, it exists in every culture in different forms.

Orientalism (noun)

1. Style, artefacts, or traits considered characteristic of the peoples and cultures of Asia.

2. The representation of Asia in a stereotyped way that is regarded as embodying a colonialist attitude.

Recommended for you: 10 Great Japanese Horror Movies

By Kat Lawson