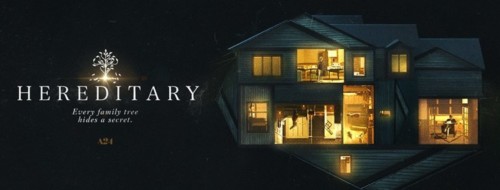

Hereditary (2018) Review

Hereditary (2018)

Director: Ari Aster

Screenwriter: Ari Aster

Starring: Toni Collette, Alex Wolff, Milly Shapiro, Gabriel Byrne, Ann Dowd

I’m a massive scaredy cat, but I’m a cat that enjoys the fright, so I agreed to go and see the new hot horror film Hereditary with my sisters. I don’t really watch TV anymore these days, so it was surprising that I’d managed to be exposed to the trailer for this film so many times (thank you Instagram and your basic advert algorithm). But I was, and I liked what I saw, which was mostly Toni Colette and Gabriel Byrne. However, everything I was expecting from the trailers was thrown out the window after about 20 minutes into the running time… and I loved it!

If you’re a hardcore horror fan, then this may not be the film for you. There are no real scares and the gore is somewhere close to a minimum. Instead, Hereditary is more of a psychological thriller filled with signals and foreshadowing similar to a Fight Club as opposed to something like one of the bloody Halloween sequels – it’s the kind of film where you realise the importance of what seemed like cliche throw away dialogue after it’s over.

All you film nerds out there will really enjoy reading up all the theories and explanations after you’ve sat down to watch it.

The film opens with the death of Ellen, the mother of central protagonist Annie. At the funeral, we are told how secretive Ellen was, and how Annie and her family seem to be completely estranged from her, furthered by the fact that none of the family members seem to be visibly upset by her passing. None of them that is, other than Annie’s daughter Charlie. Early on in the film we are made aware of the fact that Ellen had an unnaturally close relationship with her granddaughter; a fact made clear in the purposefully misleading trailer. Yet, instead of Ellen haunting her family through her beloved grandchild as the trailer further suggested, the story instead delves into the horror of sanity. The three other members of the family Annie, Steve and Peter seem to be almost frigidly unaffected by Granny’s death, but end up being the people most impacted by it.

The film jumps in and out of dream sequences and hallucinations which are beautifully emphasised in the cinematography. We are often brought back to the Macabre miniature art that Annie creates as a full-time artist, with the very first shot of the film being a slow zoom towards what appears to be a doll’s house, but is revealed as the life size room of Peter. From the very beginning we are aware that we are meant to be unsure of what is reality to the characters; what they are living and what they are dreaming. The miniature sculptures are also used as a clever story telling device. Often important memories and events that are mentioned by Annie are later seen in miniature form dotted around the house, evidence of the detailed, layered structure of the film’s well blended visual and written narratives. Not only does this heighten tension and mood – because they are incredibly creepy – but it helps the audience to learn and visualise important plot points that would have otherwise been put in the film as flashbacks or with the timeline starting many years earlier. This would have significantly increased the running time of the film which is already over two hours (pretty long for a film selling itself as a horror), but more importantly it would have killed the flow of the story which director Ari Aster successfully orchestrated. The miniature sculptures combined with irregular camera shots fully bring us doubt over the sanity of everyone in the picture, including ourselves, but no character more-so than the matriarch of the central family, Annie.

Toni Collette’s performance as Annie in Hereditary was unsurprisingly great. The character does not fall into the usual “mother in a horror film” trope, which helps Collette to bring her immense quality to the screen in a way we haven’t seen quite so brilliantly for years. We see her character as a woman whose harder edges stop her from smoothly filling the mould of a warm and tender parent. Annie does love her children and her husband, even insisting upon it several times during the film, but we often see Annie’s husband Steve fulfilling the role of doting parent instead. He is usually the one to offer comfort and to mediate tensions between family members, which allows for Annie to have a far more interesting character than would be typical of such a role.

We know from early on that Annie was alienated from her mother, and was not even on speaking terms with her at the end of her life despite living in the same house. As the film progresses we see that some of that parent-child estrangement has carried on to the next generation and is present between herself and her son Peter. Tangibly awkward conversations between the characters, and revelations of past trauma, combine to create an intriguing dialogue between mother and son. As previously mentioned, Annie has used her own life and experiences to inspire her artwork, but as well as aiding the picture’s more literal story progression, it also raises the question of Annie’s social skills. Some of the scenes depicted seem too personal and taboo to be made visible via her art, something that emphasises the lack of empathy in Annie. She seems oblivious to how the sculptures may affect her other family members, particularly Peter, an underlying element of Aster’s work that comes to rear its ugly head later in the picture as had been set up from the very first shot.

If you’re a fan of the original The Wicker Man, you will enjoy Hereditary. There is a sudden shift in the very last scene of the film, which seemed to come from nowhere. I’m a British Cinema goer, so public screenings hardly ever elicit an audible reaction from us stiff Brits, but there were a couple of confused squawks and “What the Hell”’s at the end of this Horror film. The pace had been similar to that of most ghost films: a creepy start with a few warm up scares to heighten the tension, finally culminating in the big scare. But in the case of Hereditary, suddenly everything goes all Wicker Man. Both films come to an end with a bizarre paradox of horror and happiness. In the final scene of The Wicker Man, Sargent Howwie is being burned alive as a human sacrifice, which to most viewers is quite alarming, yet the villagers who are watching his demise in the film itself are gleefully singing and holding hands. Hereditary has a similarly as jarring conclusion; one which is clearly influenced by the famous 70s horror.

So all in all, I went into Hereditary expecting the usual jump-scare horror film, but it instead defied my expectations. As well as a thrilling plot, Aster delves into the complex subject of mental health, giving the film so much more depth than might be anticipated. Many people may complain that there is no satisfying ending to the story, and only more questions are raised by the time the credits kick in, but if you’re so inclined to enjoy a thinker, you’ll love this. I can’t wait to rewatch this modern horror in search of all the little clues Aster wonderfully peppers throughout his production.

17/24