The Filmmaker Must Attack On All Fronts: José Mojica Marins (1936-2020)

This article was written exclusively for The Film Magazine by Paul A J Lewis of paul-a-j-lewis.com.

‘The filmmaker must […] attack on all fronts!’ – José Mojica Marins (1936-2020)

‘Making a film in Brazil is like making a spaceship and sending it to the moon. We have no resources in this country. The filmmaker must create a character. He must attack on all fronts!’

In Brazilian filmmaker José Mojica Marins’ O Ritual dos Sádicos (Awakening of the Beast, 1970), the director himself appears on a television show within the film and dispenses this advice to the interviewer and audience.

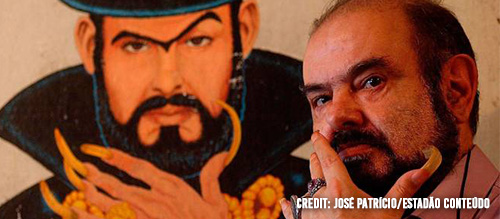

The notion of the filmmaker attacking on all fronts is arguably central to Mojica’s work. (Mojica is the name by which the director preferred to be called.) He also certainly created a character, in the form of his cinematic alter ego, Zé do Caixão (Coffin Joe) – a nihilistic undertaker with a distinctive costume of black suit, cape and top hat, whose presence anchors many of Mojica’s most well-known films. In Coffin Joe, Mojica created a character that was exploited in cinema, on television and in print; the Brazilian equivalent of Freddy Krueger or Michael Myers, Coffin Joe was born in a fever dream experienced by Mojica and has been described as a uniquely Brazilian monster.

An avowed populist, Mojica’s work is also deeply esoteric and often highly personal. In a number of films, Mojica himself appears as a character, engaging in a dialogue with his own, most famous creation. Mojica’s filmography is diverse and difficult to pin down – but unified by the filmmaker’s resourcefulness in constructing a strange, otherworldly atmosphere with minimal resources. The pictures are predominantly cheapjack but there is a clear sense of an authorial voice being developed and practiced/enacted. The films themselves are often camp but also philosophical – comparable to the work of, say, Andy Milligan, Jess Franco, John Waters or Roberta Findlay. The absurd and camp elements within Mojica’s work are often intentional, but it’s also clear that they are sometimes unintentional too.

Mojica was raised in the cinema… literally. His father managed a picturehouse in Vila Anastácio, a province in Sao Paulo; and from an early age Mojica experimented with filmmaking, shooting silent 16mm shorts with his friends which would be hand-delivered (by the filmmakers) to local cinemas. Though his films, particularly the Coffin Joe pictures, began to achieve a cult following outside Brazil in the 1990s (thanks to the work of American fans and critics), up to that point Mojica’s pictures were not distributed (officially) outside Brazil. Even today, many of Mojica’s films are unavailable in English-friendly editions, and the analogue materials used for previous home video releases are reputedly in terrible shape. Mojica would often struggle to find financing for his features, and would rely on the profits of his previous films to both live and kickstart his next feature; so when his films faced censorship problems – such as, most notably, with the banning of Awakening of the Beast – this would have severe consequences for Mojica’s ability to get his next project off the ground. (It is also said that Mojica’s film studios were shut down, and Mojica himself was arrested and interrogated by the Brazilian military dictatorship over the content of his films.)

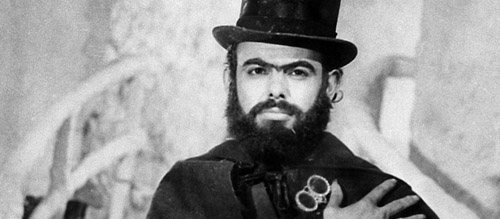

José Mojica Marins in At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (1954)

Mojica became associated with the Cinema de Boca do Lixo/Cinema do Lixo (‘trash cinema’) movement – a loose group of filmmakers whose work focused on the working class Boca do Lixo (‘Mouth of Rubbish’) region of Sao Paulo. These filmmakers didn’t have a manifesto, as such, but their work offered a reaction – at least, initially – against the rarefied approach of the Brazilian Cinema Nôvo movement. Defined by its intellectual, politicised approach to filmmaking, the Cinema Nôvo movement was influenced by the French nouvelle vague and Italian Neo-Realism. It was perhaps best defined by a saying by one of the key Cinema Nôvo filmmakers, Glauber Rocha: ‘A camera in the hand, an idea in your head’ (‘uma camera na mão, uma ideia na cabeça’). That said, legend has it that when Rocha saw Mojica’s first Coffin Joe film, À Meia-Noite Levarei Sua Alma (At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul, 1964), he was astounded by it, praising Mojica’s self-taught skills and considering Mojica to be an intuitive filmmaker. In the aforementioned television-programme-within-the film in Awakening of the Beast (‘Coffin Joe: Filmmaker or Fraud’), Mojica is introduced by a voiceover which asserts that ‘Glauber Rocha, acclaimed throughout the world as the leading figure of the New Brazilian Cinema, considers Coffin Joe a primitive artist and pure filmmaker’ – and further praise from Anselmo Duarte, another celebrated Brazilian filmmaker, that Mojica is ‘a filmmaker of undeniable talent’.

Many of the pictures of the Cinema do Lixo filmmakers were semi-pornographic pornochandada (sexploitation films) – or hybrids of pornochandada and noir, such as Rogério Sganzerla’s O Bandido da Luz Vermelha (The Red Light Bandit, 1968) – that emphasised a milieu of exploitation, sexuality and criminality. They reacted against the intellectual aesthetics and rarefied air of the Cinema Nôvo. (In 2014, an anthology film, Memórias da Boca, was produced in honour of the Cinema de Boca do Lixo era, featuring eight shorts directed by various figures associated with the movement, including Marins and contemporaries such as Alfredo Sternheim, Francisco Cavalacanti and Tony D’Ciambra.)

The films often ran into issues with the censors, especially during the period of Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964-1985). When the military dictatorship ended, some Brazilian filmmakers took advantage of the resultant cultural liberalisation by diving feet first into the production of hardcore pornography. Mojica is no exception, directing the graphic A 5ª Dimensão do Sexo (Fifth Dimension of Sex) in 1984, 24 Horas de Sexo Explícito (24 Hours of Explicit Sex) in 1985 and 48 Horas de Sexo Alucinante (48 Hours of Hallucinatory Sex) in 1987. With its sex scenes narrated by a caged parrot(!), 24 Hours of Explicit Sex features a simulated, but nevertheless graphic, scene in which an actress, Vânia Bonier, is coupled with a German Shepherd dog. Its sequel, 48 Hours of Hallucinatory Sex is equally delirious and, like many of Mojica’s other films from the 1970s onwards, highly metafictional. 48 Hours of Hallucinatory Sex focuses on a female sexologist who, having watched 24 Hours of Explicit Sex, coerces director Mojica (appearing as himself) into making a ‘sequel’ that incorporates her own erotic fantasy – being penetrated by a man dressed as a bull whilst she hides inside a wooden cow.

Awakening of the Beast (1968)

Particularly notable in Mojica’s filmography is the 1968 Coffin Joe picture Awakening of the Beast, which intersperses clips from a fictional intellectual television programme in which a confused and bemused Mojica is a guest – serious talking heads, shot in sharp chiaroscuro, talking about the impact of narcotics on Brazilian culture – with vignettes depicting the lurid stories of urban degeneration and exploitation that the panel are discussing. Only eventually linking back to the Coffin Joe character in its final sequences, these are stories of drug abuse, prostitution, various sexual perversions, criminality, police brutality, experiments with LSD, and out-and-out weirdness. Awakening of the Beast was banned in Brazil, the authorities apparently terrified by the idea that Mojica’s film was highlighting a social issue (drug culture and drug addiction) that they were trying to sweep under the proverbial carpet.

‘How do your films contribute to the Brazilian cinema?’, the television interviewer in Awakening of the Beast asks. ‘By creating plenty of jobs and giving audiences what they want’, Mojica replies. Ironically, though Mojica’s populist exploitation films are best understood as a reaction against the Neo Realism-inspired Cinema Nôvo, many scenes in Mojica’s films, thanks to their low budgets and use of non-professional actors, bear some similarities with the work of European filmmakers such as Pier Paolo Pasolini. When Mojica pans across the eccentric faces of the townsfolk, framed in close-up, in the first two Coffin Joe films (At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul and 1967’s Esta Noite Encarnarei no Teu Cadáver/This Night I’ll Possess Your Corpse), for example, the viewer might be forgiven for thinking that they have accidentally switched to one of Pasolini’s pictures – Accattone (1961), perhaps. Faith and constrictive morality are further themes that link Mojica’s work with that of Pasolini, with both filmmakers being declared atheists who nevertheless explored the dominance of Catholicism in their respective (Italian and Brazilian) cultures.

Railing against the blind faith of Christianity, Coffin Joe originated in a magazine/photo-comic, “O Estranho Mundo de Zé do Caixão” (“The Strange World of Coffin Joe”), which was a collaboration between Mojica and the writer Rubens Francisco Lucchetti. Thus Mojica’s Coffin Joe films already had an established audience and were popular with the Brazilian people. The Coffin Joe films are essentially about Joe’s belief in what he called the ‘immortality of blood’. In the first Coffin Joe picture, At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (1964), undertaker Joe rails against Christianity, performing a series of irreligious acts – beginning with a desire, which quickly develops into a rage, to eat lamb on Good Friday as the faithful perform their ritual Walk of Witness outside (‘What do I care if it’s Holy or the Devil’s Friday? I’ll get what I want, and no Bible thumper will stop me’), and escalating to gambling on a holy day, rape and cold-blooded murder. By the end of the series, in Embodiment of Evil (2009), the atheistic Joe has evolved and, in the later films, is himself depicted as a figure comparable to Satan, presiding over a Hellish inferno of torture and degradation. Coffin Joe is undoubtedly an utterly reprehensible character – cruel and sadistic, utterly self-interested and with a misogynistic streak that is more than a mile wide – but at the same time, his vein of anti-authoritarianism and individualism no doubt spoke to audiences who were experiencing the repression of Brazil’s military dictatorship.

At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (1964)

At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul opens with Coffin Joe, dressed in his trademark black suit, cape and top hat, addressing the camera directly, expressing the philosophy that motivates him throughout this picture and Mojica’s subsequent films about the character. ‘What is life? It is the beginning of death’, Coffin Joe tells the film’s audience, ‘What is death? It is the end of life. What is existence? It is the continuity of blood. What is blood? It is the reason to exist’. An atheist, Coffin Joe is introduced presiding over a burial, in his role as undertaker. He is driven to perpetuate his bloodline – to find the ‘perfect’ woman who will bear him a son. His lover Lenita (Valeria Vasquez) is unable to do this, so he kills her. Setting his sights on Terezhina (Magda Mei), the fiancé of his best friend Antonio (Nivaldo Lima), Coffin Joe murders Antonio whilst mocking his friend’s Christian faith. (‘What was all that faith for? I am stronger than you’, Coffin Joe mocks after bludgeoning Antonio and drowning him in a bathtub.) Coffin Joe then rounds on Terezinha, assaulting and murdering her. In the film’s climax, Coffin Joe is dragged to Hell by his victims, all the while espousing his nihilistic philosophy. ‘I want the end of the world’, he rages, ‘Nothing exists but life! Nothing is stronger than my disbelief!’

In the second Coffin Joe picture, This Night I’ll Possess Your Corpse, Coffin Joe wanders into another small town and establishes a new business as an undertaker, mocking the faith of those he sees around him. In this film, in comparison with the low-key rural Gothic of At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul, Joe is portrayed as almost like a mad scientist, with an underground lair filled with instruments and an Igor-like assistant named Bruno (Jose Lobo). ‘People are always the same’, he asserts, ‘ignorant, superstitious, inferior [….] Man in his stupidity can’t comprehend the only truth of life: the immortality of blood’. Coffin Joe abducts six women, holding them captive in his lair, a network of cells and various torture chambers. Joe subjects the women to a series of tests, with the intention of deciding which of them is the most fearless – a trait which he hopes to find in the prospective mother of his child. (‘My child will grow in the womb of a superior woman’, he asserts.)

This Night I’ll Possess Your Corpse (1967)

Reworking the narrative of the first film as much as functioning as a direct sequel to it (in a manner comparable to the relationship between Sam Raimi’s 1981 The Evil Dead and the 1987 sequel Evil Dead II), This Night I’ll Possess Your Corpse offers Coffin Joe a space to expand his philosophy, which by this point in the broader narrative has become Nietzschean. Coffin Joe sees himself as part of ‘a superior race. A race that will become immortal through the control of instinct’. For Joe, ‘Those who love are weak. Love corrupts the soul, so it’s a bad feeling’. He is obsessed with the concept of the Nietzschean Superman, believing that the suppression of instinct will be the next step in evolution, and it is in this film that Coffin Joe’s misogyny becomes most apparent. He torments the women he captures with spiders and snakes. In one sequence, he sends an army of huge spiders into the rooms in which the women are sleeping; we see the spiders – and these are clearly not the patently fake pipe-cleaner prop spiders used, for example, by Lucio Fulci in …E tu vivrai nel terrore! L’aldilà (The Beyond, 1981) – crawling over them. Mojica films in loving closeup the creatures crawling over the limbs, torsos and faces of his actresses. ‘A little scare to measure your courage’, Coffin Joe mocks. In another scene, one of the women is placed in a room filled with snakes. It’s said that Mojica would hold open auditions and subject his actresses to these torments, testing their mettle before dishing out the respective roles. Certainly, Coffin Joe emerges as a deeply misogynistic character (‘Man is ruler of life, and woman is his instrument’, Joe declares in Awakening of the Beast); it’s perhaps too easy, given the confusion in popular culture between Coffin Joe and Mojica, to ascribe that trait to Mojica himself.

By the late 1960s, Coffin Joe had lodged himself in the collective unconscious of Brazilian film culture, to the extent that Mojica was becoming confused with his creation. From Awakening of the Beast onwards, a number of Mojica’s films focus on separating the art from the artist. Mojica appears in some of these films as himself, often frustrated that other characters confuse him with his creation, Coffin Joe. In Awakening of the Beast, Mojica is sneered at by the other members of the television discussion panel – a psychiatrist and a journalist – one of whom directly criticises Mojica for ‘not having the intellectual capacity’ to understand the debate about drug culture that is taking place, before making the mistake of referring to Mojica as ‘Coffin Joe’. ‘Excuse me, but Coffin Joe stayed behind’, Mojica asserts, ‘You’re talking to José Mojica Marins’. Mojica reminds the others that he is not Coffin Joe, establishing a distance between himself and his fictional creation – and suggesting that the authorities’ attempts to blame Coffin Joe for the misbehaviours of young people are misguided. Mojica rejects attempts to link his worldview with the misogyny and nihilism of his fictional creation: ‘He’s a sadist, a degenerate, the Devil incarnate’, he reminds the other members of the panel.

Hallucinations of a Deranged Mind (1978)

A similar theme is explored in the mostly disappointing Delírios de um Anormal (Hallucinations of a Deranged Mind, 1978), which for all intents and purposes is little more than a ‘greatest hits’ compilation of footage from the previous Coffin Joe films, strung together by the barest of plots. In Hallucinations of a Deranged Mind, a psychiatrist, Dr Hamilton (Jorge Peres) becomes obsessed with the idea that Coffin Joe is trying to steal Hamilton’s wife Tânia (Magna Miller), seeing in her the ‘perfect’ woman to carry his (Joe’s) child. Much of the film is comprised of tight close-ups of the institutionalised Dr Hamilton, against a plain black backdrop, interspersed with footage from Mojica’s other Coffin Joe pictures – like an extended exercise in the Kuleshov effect. (To compound this, this footage is clearly shot on varying types of film stock which is in equally varying stages of decomposition, resulting in material which doesn’t match and in fact often jars.) Mojica himself is called by the psychiatrist caring for Hamilton, in the hope that Mojica’s appearance to Hamilton will disprove the existence of Coffin Joe – proving to Hamilton that Coffin Joe is a fictional character. At this stage in the bigger narrative of Coffin Joe, the character has morphed from an atheist into the Devil himself, presiding over the tortures of Hell. As a conventional narrative feature, Hallucinations of a Deranged Mind is an odd beast, comparable to the way in which Spanish filmmaker Jess Franco would sometimes recycle footage from previous films in order to make a ‘new’ feature – for example, in Neurosis: The Fall of the House of Usher/Revenge in the House of Usher (1983) or the manner in which Franco, in several films, reworked footage from Exorcismes et messes noirs (1975) in the hardcore feature Sexorcismes (1975) and the much later horror-noir hybrid L’éventreur de Notre-Dame (The Sadist of Notre-Dame, 1979).

What is arguably Mojica’s best horror film, Exorcismo negro (Bloody Exorcism, 1974) is also his most reflexive, the ‘exorcism’ referred to in the film’s title undoubtedly an attempt to capitalise on the international film culture fallout of William Friedkin’s 1973 film The Exorcist – but also suggesting that Mojica was using the film to exorcise himself of Coffin Joe. In this film, Mojica establishes at once a separation from, and kinship with, his own creation. Predating the likes of Lucio Fulci’s Un gatto nel cervello (Cat in the Brain, 1990) and Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994), Bloody Exorcism sees Mojica, appearing as himself (ie, as José Mojica Marins, the filmmaker), directly confronting his work and its legacy. (As an aside, Bloody Exorcism is also one of the most unusual Christmas-set films ever.)

Bloody Exorcism (1974)

Bloody Exorcism opens on a young couple in a dingy urban flat, sharing a bottle of wine. A pair of masked thugs break into the flat, attacking the young man and sexually assaulting his girlfriend. However, much to the horror of the attackers, the ‘victims’ in this scenario suddenly transform into hideous monsters. Just as the viewer has settled into watching a cheapjack, somewhat conventional horror film, the poverty of its production established in the single and singularly unimpressive location, a voice asserts ‘Cut’ and we cut to Mojica in the director’s chair, his camera crew scattered around him – and the viewer realises that the action they have seen unfold is material for a film-within-the-film.

We follow Mojica to a press conference, where he is asked by a journalist, ‘Who is more important: José Mojica Marins or Coffin Joe’. ‘Coffin Joe does not exist’, he reminds the gathered reporters (at which point a spotlight explodes suddenly, an omen of supernatural things to come), ‘I just used my body, my physical self, to communicate an idea’. Mojica plans to make a film called The Demon Taker, about an exorcism. However, to research and write the script he intends to retreat, over the Christmas period, to the country house of a friend, Alvaro (Walter Stuart). We follow Mojica’s journey by boat to this house, his voyage accompanied on the soundtrack by choral music. This sequence is quietly unsettling owing to the steady movement from a claustrophobic urban spaces to open rural locations – and perhaps unintentionally reminiscent of Marlowe’s journey in Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”. Certainly, there’s a sense of Mojica echoing the 1816 visit to the Villa Diodati by Byron, John Polidori and the Shelleys that led to the birth of John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” and Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus”.

At Alvaro’s house – where Alvaro lives with his wife and children, Betinha, Vilma and Luciana – Mojica experiences various supernatural phenomenon culminating in the apparent possession of Alvaro’s father, Julio, and Alvaro’s daughter, Vilma. Chairs move by themselves; a statue of Christ is decapitated suddenly. ‘It’s interesting’, Mojica notes, ‘Seems like nature itself gets angry when I deny the existence of Coffin Joe’. These supernatural events, largely lensed via the disorientating use of an extreme wide-angle lens, escalate; and it is revealed that Vilma is betrothed to Eugenio, the son of a local witch, who is also rumoured to be the son of the Devil (Coffin Joe) himself. (To make matters more complicated, it is also revealed that Vilma is the daughter of the witch, and Alvaro and Lucia – who at the time were unable themselves to conceive a child – were given her under the proviso that when she came of age, she would marry Eugenio, her own biological brother.)

Along the way, Mojica gives voice to ideas about his films which may or may not be the director’s own. (With the level of irony evident in this film, it’s difficult to tell.) He suggests that horror films are a form of catharsis, an extension of the fairy tales of childhood. ‘I’m a simple creator of fantasy’, Mojica says, ‘Good and Evil are characters in my work’. At the climax of the film, Mojica comes face to face with Coffin Joe himself, who has evolved from a devout materialist and atheist into the Devil. (Mojica’s pale pink lounge suit, a signifier of luxury, contrasts sharply with the costume of Coffin Joe – his trademark black suit, top hat and cape.) Coffin Joe presides over a Black Mass, directing the participants like the director of a motion picture. (‘Spill the blood of those who do not deserve to live!’, he orders.) This ceremony is to culminate in the marriage of Eugenio and Vilma, and the sacrifice of Alvaro’s youngest child, Betinha. During this ceremony, Mojica witnesses a litany of cruelties: people are dismembered, their body parts and organs cannibalised; tongues are torn out; ears are cut off. Finally, when the ritual builds towards the sacrifice of Betinha, Mojica takes action, confronting Coffin Joe with a crucifix (‘You’re a creation of my own mind!’, he cries out), rescuing Betinha and the other members of Alvaro’s family from Coffin Joe with a symbol of faith, reinforced by Mojica’s stated declaration, ‘I believe in God!’ This is certainly an interesting denouement for a filmmaker who claimed to have walked away from his Catholic faith in 1963, following an unpleasant encounter with a priest who apparently cursed Mojica when Mojica arrived late for Mass.

Mojica’s approach to narrative is freeform; his filmmaking methodology is experimental, probably in no small part owing to his lack of formal training. (‘I don’t think you can learn cinema by simply studying it’, Mojica asserts in the 2001 documentary Maldito – O Estranho Mundo de José Mojica Marins/The Strange World of José Mojica Marins, directed by Andre Barcinski and Ivan Finotti.) The films, particularly At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul and This Night I’ll Possess Your Corpse, draw visually on Expressionism and Surrealism. This Night I’ll Possess Your Corpse, a film shot in monochrome, features a sequence in which Coffin Joe is drawn down into Hell itself, which is photographed in lurid colour. Similar ‘bursts’ of colour appear in Awakening of the Beast and Mojica’s other monochrome features, the juxtaposition of monochrome and colour photography often intentionally jarring – functioning in an almost Brechtian manner. In the early monochrome films by Mojica, these colour sequences invariably depict visions of Hell – reinforcing the taboos that the Coffin Joe transgresses. Though Joe’s nihilism may seem liberating – especially, as noted above, in the context of the Brazilian military dictatorship – he is invariably punished at the ends of each narrative, his vicious energy contained and recuperated, often by a journey into Hell itself. With each film, the character evolves – from the first few films, in which Joe is depicted as an utter materialist, to the later entries in which the character has become like the Devil himself, a supernatural entity presiding over the tortures of Hell. In this sense, the films are profoundly Catholic, though Mojica himself had a messy relationship with faith: he claims in The Strange World of José Mojica Marins that he was a devout Catholic until 1963. The incident of the priest and the curse changed Mojica’s outlook on faith forever, though within his subsequent films there is often a battle between faith and faithlessness (or anti-faith, as expressed by the character of Coffin Joe).

Given the confusion of Mojica and Coffin Joe, it’s too easy to ascribe some of Coffin Joe’s qualities to Mojica (for example, his nihilism and his misogyny) himself; and this (the ease with which the artist can become confused with their art) is something that is at the core of Mojica’s most memorable films – Bloody Exorcism and Awakening of the Beast, in particular. Within Mojica’s cinema generally, there’s a sense of resistance through the challenging of taboos – which is comparable, perhaps, to Spanish filmmaker Jess Franco’s work during the Francoist dictatorship. Like Franco, Mojica seemed to lose his way somewhat once the repressive regime in which he lived had been lifted. (Both filmmakers ended up making, during the 1980s, often taboo-busting but generally quite tedious hardcore pornography – as if once the respective repressive dictatorships in which they lived had ended, the need to try to kick against the proverbial pricks could only be exorcised by pushing boundaries in porn. Mojica claims, again in The Strange World of José Mojica Marins, that he made these pornographic films solely ‘to survive’.)

There is an utter audacity in Mojica’s approach to cinema. In the mid-1970s, he filmed the surgery he had on his own eyes, directing the cameraman whilst the surgeon was working with his scalpel, and used this footage to enliven his otherwise unmemorable thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana pastiche Inferno Carnal (Hellish Flesh, 1977). The footage is grotesque and sticks in the craw, despite the humdrum nature of the narrative into which it is placed. (The story revolves around a revenge plot enacted by a scientist, played by Mojica, who is scarred with acid thrown into his face by his unfaithful wife.) Mojica’s outrageousness in terms of his films was matched by his apparent naivete in terms of business practices. ‘I never got rich because I lived like a poet’, he says in The Strange World of José Mojica Marins, ‘I didn’t care too much for money. I never thought about the future’. The films themselves are variable in quality; some (such as Hallucinations in a Deranged Mind) are quite dire. However, they again bear comparison with Jess Franco’s work in the sense that once one has seen a good number of them, a much bigger narrative evolves. In “How to Read a Franco Film” (published in the first issue of Video Watchdog), Tim Lucas once said about Jess Franco, ‘You can’t see one Franco film until you’ve seen them all’; the same is arguably true of Mojica. In a world where repressive regimes clearly don’t go away but simply evolve, assimilate and migrate, we might wonder where the kind of cinematic resistance we see in Mojica’s work will next appear.

Written by Paul A J Lewis

You can support Paul A J Lewis in the following places:

Website – paul-a-j-lewis.com

Twitter – @Krycek_Facility